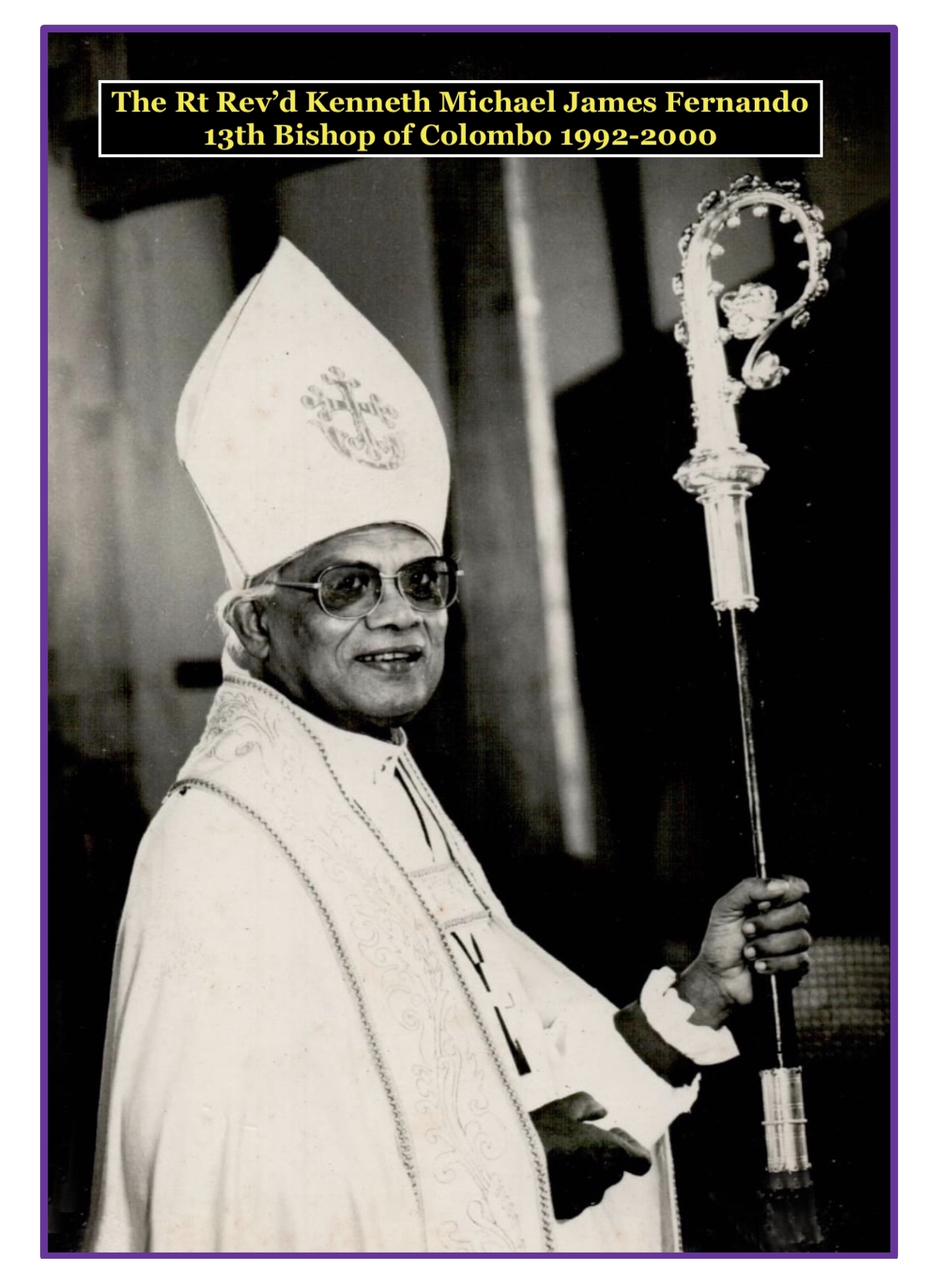

In Memoriam Bishop Kenneth Fernado

AUDACIOUSLY ANGLICAN AND A BISHOP FOR ALL SEASONS

The Rev’d Marc Billimoria is an ordained priest in the Diocese of Colombo of the Church of Ceylon (the Anglican Church in Sri Lanka).

Marc has a 1st Class B.A. in History from the University of Pune, India and a MTh from the University of Wales Trinity St David, Lampeter.

He trained for the priesthood at Ripon College Cuddesdon, Oxford.

After 24 years of ministry in Sri Lanka, 17 of which were in diocesan school leadership,

he is now on sabbatical in Melbourne, Australia, where he is working on a full-time PhD

from the University of Divinity at the Trinity College Theological School.

“For you, I am a bishop, with you, after all, I am a Christian”

St Augustine, Bishop of Hippo[i]

The Right Reverend Kenneth Michael James Fernando, 13th Bishop of Colombo from 1992 to 2000, was the quintessential Audacious Anglican who always tried to hold in balance (and often in tension) the different expressions of the Anglican Way while also courageously exploring new directions in theology, mission and ministry for the Church to be relevant as it engaged in the missio dei.

‘Audaciousness’ is a word used to describe a person who is ‘intrepidly daring’, ‘adventurous’ and ‘willing to take risks’. It is a word that is not misplaced in its application to the subject of this tribute that was originally written for the festschrift celebrating his 90th birthday and also the 30th anniversary of his consecration as a Bishop in the Church but which is now a tribute to his memory on his passing away on 3rd September 2025.

JOURNEY TO THE EPISCOPATE

Born on St James’ Day, 25th July 1932 and hailing from an Anglican family in Moratuwa, Bishop Kenneth was educated at Trinity College, Kandy (1937 – 1941), St. John’s College, Panadura (1941 – 1942), Prince of Wales’ College, Moratuwa (1943 – 1945) and Royal College, Colombo (1945 – 1951) before going on to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree with Honours in Western Classics, Greek and Latin from the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya (1951 – 1955).

Having been accepted by the Rt. Rev’d Archibald Rollo Graham-Campbell, 7th Bishop of Colombo, as an aspirant for the ordained ministry, he was sent to Cuddesdon Theological College in Oxford, England where he received his ministerial training and formation (1955 – 1957) under the legendary Principal Edward Knapp-Fisher who presided over what was then perhaps the premier Theological College of the Church of England and the Anglican Communion. Knapp-Fisher’s tenure as Principal was one in which Cuddesdon became known for a strict, almost rigid regimen in which a disciplined lifestyle was expected of the ordinands in training.

At the end of his time at Cuddesdon, he was made a Deacon by Bishop Michael Gresford-Jones of St Albans in St Albans Abbey Church and Cathedral on 22nd September 1957. He served his curacy at St. Luke’s Church, Leagrave, Luton within the Diocese of St Albans (1957 – 1959) where he was also ordained to the priesthood by the Bishop of Colombo, on 17th August 1958 by Letters Dimissory, while Bishop Archibald was in England to participate in the Lambeth Conference of 1958.

Returning to Ceylon in 1959 he was appointed to serve as Assistant Curate of Christ Church Cathedral at Mutwal, based at St John’s Church nearby, before going in 1960 to be Vicar of St. Mark’s Church, Badulla. In 1966 he was appointed Resident Director of the Suddharshana Centre at Buona Vista in Galle where he served until 1972. From 1972 to 1978 he was Secretary of the Diocese of Colombo, the last clergyman to hold that office. During his tenure, he not only reorganized the administrative systems of the Diocese, including being part of the decision that changed the clergy transfers and appointments methodology, he also gained much experience in Diocesan administration.

From 1978 to 1984, he served as Vicar of St Luke’s Church, Borella, an evangelical parish that had been established by the Church Missionary Society, where he developed the outreach work of the Parish and also transformed the liturgical life of the worshipping community there. Inspired as he was by the liturgical movement that followed the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, he brought the altar to a more central position in the sanctuary, so the presider was able to face the people when celebrating. This reform also provided for the communicants to kneel all round to receive the Blessed Sacrament, as it had been done at the new Cathedral of Christ the Living Saviour, the final design of which had been proposed by a group of clergy in 1965 of which he had been a member.

From 1984 to 1992 he was Director of the Ecumenical Institute for Study and Dialogue[ii], given his commitment to ecumenical and wider-ecumenical dialogue.

Elected 13th Bishop of Colombo he became the first to be episcopally ordained by an Archbishop of Canterbury in Sri Lanka itself when the Most Rev’d George L. Carey visited the island as Metropolitan of the Church of Ceylon to perform the task in what was a moving and appropriately indigenous act of worship in the Cathedral of Christ the Living Saviour on the Feast of St Nicholas of Myra, 6th December 1992. His election in 1992 gave the Diocese of Colombo a Bishop for the times. It was a kairos moment as both the Church and the Nation needed a leader with his particular skills, personality and charisms to be an influencer for the common good, one who would encourage the mutual flourishing of all people of our country at that time.

Bishop Kenneth vacated the See of Colombo in 2000 after an eventful and fruitful tenure but continued as Vicar-General and Metropolitan’s Commissary until the episcopal ordination and installation of his successor in May 2001 after which he served as a Priest in Charge of two parishes and continued his ministry of preaching and teaching in the Diocese and wider Church until going into full retirement.

Even at the age of 90 he and his wife Chitra continued to be involved in the community in which they lived and had made their home. He was active in the affairs of the Diocese offering his counsel and guidance as and when invited to do so in recent years proving the adage, “Once a Bishop always a Bishop!” His most recent official roles include being authorised by the Metropolitan of the Church of Ceylon to be one of the three Bishops to preside at the episcopal ordination of the 16th Bishop of Colombo in 2020 and helping the Diocese by compiling valuable study material for parish communities in the Diocese of Colombo. This was as part of the consultation process towards the Church of Ceylon realizing its goal of becoming an independent ecclesiastical Province of the Anglican Communion.

But what of Bishop Kenneth’s contribution to the life of the Church before and during his significant episcopate? His was a ministry that included many different involvements from his ordination as a priest to his consecration as a bishop. What the Diocese of Colombo received in its 13th Bishop was a man of many facets with a great deal of experience as a churchman, theologian, ecumenist, reformer and social activist.

CHURCHMAN

When I use the epithet ‘Churchman’ I mean ‘ecclesiastic’ which refers to one who is part and parcel of the institutional Church. Despite his seemingly radical views, Bishop Kenneth was a ‘dyed in the wool’ Anglican. Did he believe in the Church Union Movement? Yes – emphatically. But this did not prevent him from remaining simultaneously faithful to the church of his birth and formation. He viewed the Anglican Church as transitional, one that had to exist until the realisation of Church Union, when it would be absorbed and become part of the united Church of Lanka.

Like Bishop Lakshman Wickremesinghe before him, Bishop Kenneth was the embodiment of an Anglican paradox as a Bishop. He combined, though at times with difficulty, his administrative role as a Bishop with a radical anti-establishment outlook on the way the Church should be run. He was keen to avoid what Bishop Lakshman had termed the “shackles of establishment” and was distrustful and impatient with structures, systems and procedures that were not life-affirming, inclusive or in the service of the Reign of God.

He was, like all his predecessors and successors, keen to ensure that his ministry as a Bishop would not tie him down to the wide range of administrative duties that have become essential for the running of the institutional Church. Thus, he had to constantly struggle to balance the pastoral aspects of his episcopal mission and ministry with the many administrative duties he had to perform. When he was consecrated Bishop in 1992 the Ordinal still had the exhortation made by the principal consecrator that a Bishop should be a shepherd to his flock: “Be a shepherd to the flock of Christ, not a wolf; feed them, do not devour them. Support the weak, heal the sick, bind up the broken-hearted, bring back the outcasts, and search for the lost. Be merciful, without being lax. Administer discipline, without forgetting mercy…”

Anglican polity is one in which the Church is “episcopally led and synodically governed”. This was a balance that Bishop Kenneth always tried to maintain. He worked tirelessly for much of his episcopate to free the Church of Ceylon from out-dated legislation that went back to 1930 and part of the enduring legacy of his episcopate is the successful passing of The Church of Ceylon Incorporation Act No. 43 by the Parliament of Sri Lanka in 1998, after many years of hard work and the overcoming of several challenges. By this Act, the Church of Ceylon, with its two orphaned extra-provincial dioceses, was legally granted autonomy and was enabled to regulate its own affairs. The immediate result was that a Constituent Assembly was formed to draw up a new Constitution for the Church of Ceylon to replace the Constitution, Canons and Rules of the Church of India, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon that had been in force from 1930. The Province had been dissolved in 1970 and the Church of Ceylon was suddenly alone being cared for temporarily by the Archbishop of Canterbury as Metropolitan in anticipation of the formation of the Church of Lanka on Advent Sunday 1972, a plan that was sadly aborted due to litigation in the civil courts. Since then, the Church of Ceylon has journeyed on as extra-provincial having to seek the blessings of a Metropolitan in a far-away land for many things including the authorization of new liturgies to the confirmation of the election of bishops. The Act of 1998, therefore, was a rekindling of hope.

In an interview with the Church Mission Society around that time, Bishop Kenneth said that the future direction of the Church of Ceylon was in one of two directions: either the fulfillment of the vision of a united Church of Lanka that would be formed on the lines proposed in the aborted Scheme of Church Union in Ceylon or the creation of more Dioceses in order to pursue the formation of an autonomous Anglican Province in Sri Lanka. As one of the key drafters of the new Constitution that finally became operative in 2007, he was able to ensure that it provided for the constitutional structures required for either of the two options.

THEOLOGIAN

Bishop Kenneth was a courageous, maverick-like theologian, and theological reflection undergirded his entire ministry. His theological position evolved as was open to the dynamic movement of the Holy Spirit in his unending quest for truth.

The foundation of his theological journey began while he was an ordinand at Cuddesdon, where he had been influenced by a new strand of Anglican theology that had its roots, particularly in the writings of Bishop Charles Gore. In 1889 a group of Oxford theological scholars led by Gore, who was then Principal of Pusey House, published ‘Lux Mundi: A Series of Studies in the Religion of the Incarnation’. They were all heirs of the Tractarian or Oxford Movement who drew insights from new scholarship and new theological trends while holding fast to the convictions they had inherited from the Tractarians who had ushered in the Catholic Revival in the Church of England and Anglicanism. This attempt at synthesising Catholic convictions with new thinking was soon called ‘Liberal Catholicism’ to differentiate it as a movement within Anglicanism from classical Anglo-Catholicism on the one hand and theological Modernism on the other. Liberal Catholics aimed at seeing “the Catholic faith in its right relation to modern intellectual and moral problems” of their day[iii]. When Bishop Kenneth began his theological education it was a movement that had reached much acceptance due to theologians such as William Temple and Michael Ramsey who were successors of Gore and his school of thought.

Bishop Kenneth was at Cuddesdon at a time when England was also facing socio-political ferment that followed the end of World War II. British imperialism was at an end as more and more colonies began to receive political independence as indeed Ceylon had done in 1948. The Cold War between the western powers led by the USA and the Communist Bloc led by the USSR was in its early days and societal norms, as well as religious beliefs, were undergoing significant changes. The horrors of World War II had left once confident Christian societies such as that in England reeling in a surge in religious skepticism and secularization of society that began to question the relevance of organized religion, faith and theology. Bishop John A. T. Robinson for example, who would later earn notoriety of sorts for his book Honest to God[iv] in which he basically argued “that our image of God must go” argued that the decline of the Church in post-war British society was due to the emergence of, what he termed, “a post-ideological society”. Theologians were seeking to respond to the sociological and cultural crises of the day. All this influenced the young ordinand opening his mind to new realities and trends.

By the time he returned home from England on completion of his curacy, the Christian world was on the brink of a second Reformation – this time from a most unexpected direction. Pope John XXIII elected in 1959, within a short time inaugurated the Second Vatican Council that ushered in a new era for not just the Roman Catholic Church but also for Western Christianity as a whole. Gaudium et Spes, the Pastoral Constitution of the Church in the Modern World promulgated by Pope Paul VI in December 1965, is a revolutionary document that transformed every aspect of the Church’s life. Vatican II had an impact on other churches too, including the Anglican Communion.

One of those who had supported Pope John’s progressive agenda was Belgian Cardinal, Joseph Cardijn, who as a young priest had founded that Young Christian Workers movement and had developed the See-Judge-Act method of Catholic Social Teaching. Pope John XXIII endorsed this method in his encyclical of 1961, Mater et Magistra, in which he wrote “There are three stages which should normally be followed in the reduction of social principles into practice. First, one reviews the concrete; secondly, one forms a judgement on it in the light of these same principles; thirdly, one decides what in the circumstances can and should be done to implement these principles.” This sort of thinking greatly influenced young priest full of passion for his ministry.

Around the same time a new, praxis-based movement in theology emerged in South America that came to be called ‘Liberation Theology’ which in turn found acceptance among theologians in many so-called Third World countries, including Sri Lanka.

At the Clergy Synod of 1966 Bishop Kenneth reported on a landmark conference that some clergy from the Diocese of Colombo had attended in Bangalore, India on the theme ‘The Significance of the New Emerging Theology’. This Conference had identified some of the signs of the times such as secularisation, urbanisation and a breakdown of community as challenges that called for creative and relevant responses from the Church. There had also been a recognition of the role of New Theology and New Theologians in this context. As the Proceedings of the Synod record the young priest: “dealt with what the Conference felt these new theologians were saying. They were far less dogmatic… They are facing up to the problem of language, by using new images and metaphors…They are far less metaphysical, and more concerned with this world and this age…They are very critical of traditional spirituality and morality…” He had also reported on how the Conference had viewed the consequences of the New Theology on the mission of the Church in a multi-faith context: “The age of missions is at an end; the age of mission has begun… The Church was discovering new frontiers of mission…It was God’s mission to the world and not man’s…The good effects of the loss of privilege in the Church due to the rise in nationalism and the resurgence of eastern religions…The mission must be Ecumenical…The Institutional Period of the Church being now at an end there was no cause for arrogance…The need of visible, intelligible, discernible ways of proclaiming the Gospel…The scandal of the Gospel is as real in this age as it was in the age of the Apostles…”[v]

Bishop Kenneth embraced the fundamentals of Catholic Social thought that emerged from Vatican II and from the New Theology such as a strong emphasis on human dignity, the common good and solidarity. He was soon recognized as a theologian who while standing firmly on the faith once entrusted to the saints was not afraid to explore theology at the margins, even if doing so earned him the suspicion of conservatives in the Church who wrongly assumed that he was at best diluting the faith in order to make it more accessible to the modern generation or at worst engaging in syncretism in his quest for dialogue and coexistence with people of other faiths. As an academic, he continued to engage with the world of Theology and in 1971 obtained a Post Graduate Diploma in Theology from the University of Geneva.

During his tenure as its Director, the Ecumenical Institute published a book by N. Abeyasingha titled The Radical Tradition[vi]. In this valuable study, Abeyasingha examines, as the subtitle of the book states, ‘The changing shape of Theological Reflection in Sri Lanka.’ Citing D. S. Amalorpavadass, he writes that for a theologian to be effective s/he would need firstly “(i) to be involved in the reality of life and society: the world (ii) to be conscious members of the Christian community: the Church and (iii) to do an action-reflection in faith on their experience as Christians in the world: the Word.” S/he would also need to “by means of this reflection…lead both the Church and the world to the ‘eschatological goal’ of every activity of faith.”[vii] This type of theological reflection is what characterizes Bishop Kenneth’s theological outlook. Aloysius Pieris SJ has written in An Asian Theology of Liberation, “The Asian church, for the moment, has no theology of its own…” [viii] Bishop Kenneth tried to serve the cause of engaging in a self-theologizing process to contribute towards a theology for Asia as part of the movement to which both he and others have belonged to achieve just that goal.

As a Bishop, he took his apostolic ministry to be a teacher of the faith very seriously understanding it as both a privilege and a responsibility. A teacher who tried to understand and help others to try to understand God and God’s ways as revealed in Jesus Christ “the human face of God”. He sought to help the Church to re-interpret in a particular socio-cultural and historical context just how God was leading the Church in new directions while also recalling the Church back to truths that had been forgotten, neglected or even ignored. The enabling of the Augustinian and Thomist dictum Credere Deo, Credere Deum, Credere in Deum(believe that God is, believe towards or trust God, believing into God or being united with God) was never very far from his episcopal teaching ministry.

Many of his writings were included in publications both locally and internationally and in retirement he has also published a significant book of his own, Rediscovering Christ in Asia,[ix] in which he articulated his thinking and theological convictions based on his many years of ministry and engagement. His daily devotional book Through the Year with St John[x] has also been very useful to people.

Building on an idea that had first emerged during Bishop Jabez Gnanapragasam’s episcopate for the training of ordinands and the continuing ministerial education of clergy, Bishop Kenneth took steps to inaugurate the Cathedral Institute in Colombo in 1995 where ministerial candidates would receive preliminary training and formation prior to going to the Theological College of Lanka. Here those who successfully completed their time at TCL would be given pre-ordination training as ordinands and Lay Workers and Catechists could also receive basic training.

ECUMENIST

Bishop Kenneth’s ecumenical vision had been nourished at Cuddesdon. Despite being an Anglo-Catholic, the Principal of the day, Edward Knapp-Fisher, had been an ecumenist at heart and encouraged an ecumenical outlook, especially in relation to the Roman Catholic Church[xi]. This ecumenical influence is one that Bishop Kenneth would have experienced during his years of theological education and formation.

Bishop Kenneth’s ecumenical vision was of a united Church in this country. Max Thurian’s term ‘Ecumenical Servant’[xii] aptly describes his commitment to the Ecumenical Movement. Due to his Catholic conception of the Church, he was deeply committed to the goal of fulfilling Jesus’ High Priestly Prayer “that they may all be one”. Consequently he encouraged mutual flourishing between different denominations in Sri Lanka through a process of dialogue and solidarity. During his episcopate, he not only strengthened relations with the Roman Catholic Church and Churches of the National Christian Council of Sri Lanka but in 1995 he supported the formation of an Inter-Church Fellowship to facilitate dialogue and conversation between the Anglican Church and the newer evangelical and pentecostal churches to explore ways that Anglicans could walk, work, witness and worship together with them. The ICF at one of its very first conferences produced what is known as ‘The Ragama Declaration’ which sought to acknowledge shared spirituality and challenge the churches to shared presence in the community.

At an international level, he was involved with the work of the Christian Conference of Asia and served as one of its five Co-Presidents from 1995 to 2000.

His ecumenical outlook extended to wider-ecumenical activities as well. Having concluded very early on in his ministry that in countries like Sri Lanka where the Church co-existed with a number of other living faith communities, there was a need for genuine dialogue between Christians and others with a view to creating a culture of harmonious co-existence and a mutual flourishing of a different sort. Bishop Kenneth decided to study Buddhism and in 1986 completed a Diploma in Pali & Buddhist Studies from the University of Kelaniya. His passion for wider ecumenical inter-faith dialogue and especially dialogue with Buddhism was one of his priorities as Director of the EISD, inspired no doubt by his association with Aloysius Peiris SJ and Lynn de Silva, whom he succeeded as Director.

In his Gerald Weisfeld Lecture of 2004 ‘Buddhism, Christianity and their Potential for Peace: A Christian Perspective’, delivered at the Centre for Inter-Faith Studies of the University of Glasgow in May 2004, Bishop Kenneth articulated his vision for Buddhist – Christian Dialogue flowing from his personal experience of Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka and his close involvement with like-minded Buddhist monks pursuing peace in a country torn apart by an ethnic civil war. He writes there, “All religions throughout human history have been and indeed still are sources of conflict. But they can also be resources for peace. But this will require that the religions we believe in should not confine us to our respective camps but set our human spirits free – free to explore all that is good, beautiful and true in human experience; free to seek partners and colleagues wherever they may be found; free to reach out towards true human community and peace and all that makes for what is best and worthwhile in human life.”[xiii]

Having served as a Co-Chair of Section 1 (Called to Full Humanity) of the Lambeth Conference of 1998 that dealt with a wide range of important issues such as ecology, human sexuality and religious freedom among others, he was soon appointed one of the Co-Chairmen of the Network for Inter-Faith Concerns[xiv]. He remained a Co-Chair until he vacated the See of Colombo in 2000. His intimate knowledge of Buddhism and of the dialogue between Christianity and Buddhism in Sri Lanka served him well in this role too. NIFCON was based on four essential principles of Dialogue that had originated with the World Council of Churches and had been adopted by Resolution 20 of the Lambeth Conference:

- Dialogue begins when people meet people.

- Dialogue depends upon mutual understanding, mutual respect and mutual trust.

- Dialogue makes it possible to share in service to the community.

- Dialogue becomes a medium of authentic witness.[xv]

Abeysingha has identified two forms of Christian – Buddhist Dialogue in Sri Lanka: the first is a form of dialogue that aims at finding links and similarities between Buddhism and Christianity so that the Christian Gospel could be communicated couched in a Buddhist form. The second is far more radical and it is a form of dialogue by which Christians actually seek “to learn from Buddhism, to examine its phenomenology and values” and join with Buddhists “in their struggle for the integral liberation of man.” [xvi] It is with this second school of dialogue, “the Dialogue of Mutual Enrichment” that Bishop Kenneth was in most sympathy.

Even in retirement, he continued to hold this larger vision that embraces the diversity of faiths, beliefs, cultures and religious traditions that makeup Sri Lanka. In this, he was heir to a long line of Sri Lankan Anglicans going back to James D’Alwis and Isaac Tambyah who were lay scholars of Buddhism and Hinduism and pioneering advocates of inter-faith dialogue towards building harmonious coexistence while at the same time exploring a new understanding of the way the Church must engage in mission in a multi-faith society.

REFORMER

Despite his early education and formation from the inception of his ministry he has advocated, along with others, both lay and ordained, an Anglican Church in this country that would be a truly Sri Lankan Church: a “self-supporting, self-propagating, self-expressive and self-reliant indigenous Church in Sri Lanka”[xvii] that many of his contemporaries in the field of theology and pioneering organizations such as the Christian Workers’ Fellowship of Sri Lanka were working for as well. He supported not just the movement to indigenize the liturgies of the Church but also one in which the Church would engage in a process of self-scrutiny to become more autonomous from its colonial past while engaging in the very necessary task of self-theologizing as well.

An early example of his reforming zeal was his involvement in changing the plans for the new Cathedral for the Diocese of Colombo. Plans for a new Cathedral had first been mooted in 1910 but nothing had happened for years. In 1940 the Diocesan Council had elected a New Cathedral Committee. In November 1945 the foundation stone was laid for the Cathedral of the Holy Cross as part of the centenary celebrations of the Diocese. This was followed by a further period of dormancy until Bishop Harold de Soysa’s episcopate when he revived the plans and began to call for changes to the plans. A petition signed by Canon W. H. W. Jayasekera, the Rev’ds Celestine Fernando, A. J. C. Selvaratnam and Kenneth Fernando, was presented to the Bishop at the Clergy Synod of 1966 expressing concerns about the design that had been promoted up to then, which was on the lines of cathedrals and churches built in England, and calling for an entirely new design in keeping with new ecclesiological, theological and liturgical realities[xviii]. In the discussion that followed, Bishop Kenneth, perhaps the youngest among the group at that time, is recorded to have said, “there was all too often a deep cleavage between thought and action in our Church, and this was evident in the present design for the new Cathedral. The image of the Church that those outside will get will be conditioned by the Cathedral. Apart from the fact that it could be criticised on liturgical grounds, the present design was a symbol of power and esteem…”[xix] The Bishop upheld the petition and permitted the group of clergy to bring a Resolution at the Diocesan Council to re-appoint a New Cathedral Committee with a view to looking at a new Design – one that would be simpler which, in the words of the petition, “will be liturgically contemporary, socially useful and evangelistically significant.” Writing in an article published in the Ceylon Churchman in 1967 titled ‘Cathedral Building in Modern Lanka’[xx] Bishop Kenneth made an impassioned plea to the New Cathedral Committee to review its plans for the new Cathedral, the work on which was shortly to commence. He wrote, “A Cathedral is never a monument or a memorial; it is always a symbol, a symbol of what the Christian community believes about themselves, their age and the nature of their community and their worship.” Needless to say, the influence of visionary clergy like him did have an impact on those entrusted with the task of designing the new Cathedral and many of the ideas he proposed were incorporated into the final building.

His zeal for reform also extended to his conviction about the ministry of the whole People of God. His Catholicity has also inspired his stance for a truly inclusive Church in which the full participation of all in the Church’s life and ministry and opportunities for the mutual flourishing of all has been the goal. Consequently he, and his wife Chitra, were pioneering voices in the movement for the ordination of women both before and during his elevation to the episcopate. At the Diocesan Council of 1983, he joined hands with the Rev’d James Ratnanayagam to move a resolution calling on the Bishop to initiate a study, process of dialogue and necessary action to help the Diocese to move forward on the controversial issue of the Ordination of Women. As a result, the Bishop appointed a Commission of which Bishop Kenneth was appointed Chairman and Mrs Myrtle Mendis served as Secretary. This Commission presented its findings in the form of a Report in October 1985 and courageously recommended that the ordination of women to all three orders of ministry be allowed but to the Diaconate with immediate effect and to the other two orders in stages as the Church continued to grow with the idea. It was only in 2003 after he had retired that Bishop Kenneth was to see the fruit of his labours.

SOCIAL ACTIVIST

Bishop Kenneth’s conviction that the quest for human dignity and acting in solidarity for the common good of all must be the cornerstone of Anglican social theology is based on his belief the Incarnation and on the principle of Genesis 1: 26 that God has created every human person in God’s image and likeness. As such he constantly sought to oppose all that dehumanizes other human beings as evil. For Bishop Kenneth these foundational principles of Anglican social thought resulted in an activism of solidarity for the common good such as opting for the poor and marginalized (the preferential option for the poor), striving for economic justice, working for the care of God’s creation and ecological justice. These for him are non-negotiables in the task of mission.

Despite his love of liturgical worship, Bishop Kenneth over the years rejected a merely pietistic or mechanical form of worship limited to the ritual and ceremony of Anglican Liturgy. He followed in the tradition of Anglican social vision that is itself rooted in the Christian Socialism of F. D. Maurice and the Catholic Social Union of Henry Scott Holland and Charles Gore as well as in the historic ministries of the Slum Priests, Stewart Headlam, Conrad Noel, and Kenneth Leech, as well as the sacramental socialism of many of his Sri Lankan Anglican contemporaries in the field of contextual theology and social action such as Bishop Lakshman Wickremesinghe, Sevaka Yohan Devananda and Vijaya Vidyasagara.

The Holy Eucharist was to be for him not just the source of spiritual power and union with Christ but also a foretaste of the great and joyful eschatological banquet to come at the consummation of all things. He believed that the Eucharist is the springboard for mission and ministry to the world and the sacred meal of the Reign of God. The Eucharist and life are intertwined and lead to a form of social activism that characterised his life and ministry as a priest and a bishop in the Church. In his own words, he had always “tried to become a Eucharistic person”.[xxi]

The Kingdom or Reign of God was always central to his mission and ministry believing as he did, “that the main thrust of the mission of Jesus was the establishment of the Kingdom of God.”[xxii]

Bishop Kenneth like many Asian Theologians of his generation called for holistic and integral mission and evangelization, not merely concerned with the salvation of souls in a spiritual sense but also for the liberation of people while they continued their earthly pilgrimage so they could enjoy the fullness of life and freedom with dignity and justice. Bishop Kenneth believed in the need for the Church to engage in self-scrutiny and self-criticism in its quest to be the agent of the Reign of God and supported the need for radical change in the way the Church lives and serves.

This is the thinking that influenced his own socio-political views that took shape at University and at Theological College and perhaps blossomed when he served at Buona Vista during which time the Centre was used, among other things, to train school drop-outs in agriculture and farming at a time when youth, especially in the south were turning to militancy to redress social inequalities. It was while he was at Buona Vista that the first Marxist youth uprising took place in 1971 with its epicenter in the south of the country.

It was this same sense of commitment to social justice that prompted him to also work for peace and reconciliation, equality and justice at a time when Sri Lanka was at the height of the internecine civil war between the Government and the LTTE. The Christian Church in Sri Lanka, in all its denominational expressions, is perhaps the only religious community to encompass both the main ethnic groups of Sri Lanka. As such it was a community ideally placed to engage in the peace and reconciliation ministry that the civil war had made an absolute necessity. Bishop Kenneth began his episcopate at the height of Sri Lanka’s civil war between the LTTE and the Government. One of his first official acts as Bishop was to make a visit to the Archdeaconry of Jaffna. Visiting Jaffna was by no means an easy task and he was severely criticized for his actions by some in the south but it was a courageous decision taken to express solidarity with the people of not just the Archdeaconry, but all the people of the north affected by the ongoing armed conflict. He continued to work for peace and reconciliation throughout his tenure as Bishop and was also invited by President Chandrika Bandaranaike-Kumaratunga to be part of a team sent for the fourth round of peace talks with the LTTE in April 1995. In 1999 he was part of a large group of religious leaders that included many senior Buddhist clergy, all members of the Inter-Religious Alliance for National Unity, that went to the north, including Vavuniya and Madhu and met with senior LTTE leaders in a bid to end the violence. Neville Jayaweera writing in The Role of the Churches in the Ethnic Conflict named Bishop Kenneth as one of several Christian leaders of the period who did not just speak out on the ethnic conflict but also to have “exposed themselves to the risks of praxis…”[xxiii] He quotes from Bishop Kenneth’s addresses to the Diocesan Councils of 1998 and 1999 to illustrate his point as to the depth of the involvement of the Church in trying to help solve the ethnic conflict and some of the basic principles, values and policies that the Diocese of Colombo, for instance, was trying to be faithful to during Bishop Kenneth’s episcopate[xxiv].

As Bishop Kenneth celebrated his 90th birthday and the 30th anniversary of his episcopal ordination we were mindful that above all he was himself a child of God by grace seeking after the truth. Even as St Paul in his Second Epistle to the Corinthians has written “But we have this treasure in clay jars, so that it may be made clear that this extraordinary power belongs to God and does not come from us.” So, Bishop Kenneth’s life and ministry was a very rich one during which he has experienced much and gave much to the Church, the community and the nation that he served despite his own limitations, imperfections and human frailties.

His vision for the Church so well- articulated in his article ‘The Future of our Church’ written in 1995 on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Church of Ceylon is still a challenge. His concluding words in that article read like a clarion call to action for the Church today to be a community of mutual enrichment and grace as well as a channel of blessing to our country: “Our nation looks to Christians generally to be a spiritual and moral force for good. We must preserve among ourselves a very high standard of conduct and commitment. We must spend ourselves in the service of the nation, shunning opportunities for enrichment and self-aggrandizement. We must develop a new spirituality that can come only from prayer and liturgy and deep study of God’s Word. If we are a community of God’s people totally dedicated to His purposes, we shall indeed be a blessing to the nation, a light to the Gentiles and the salt of the earth.”[xxv]

Requiescat in pace et resurget in gloria

The Rev’d Marc Billimoria

4th September 2025

[i] From Sermon 340, “On the Anniversary of His Ordination”, The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century, Translation and Notes by Edmund Hill, Edited by John E. Rotelle, Brooklyn, NY: New City Press, 1990 – 1997, pp. 292 – 294

[ii] Established as The Study Center for Religion and Society in 1951 by the Rev’d Basil Jackson, among others, in response to resurgent Buddhism following independence that brought with it the need for better understanding and dialogue between Buddhism and the Christian Church. It was renamed the Ecumenical Institute for Study and Dialogue in 1977.

[iii] Michael Ramsey, From Gore to Temple, London: Longmans, 1960, p.2

[iv] J. A. T. Robinson, Honest to God, London: SCM, 1963

[v] The Bishop’s Charge and Proceedings of Synod of the Clergy of the Diocese of Colombo, 1966, pp. 30 & 31

[vi] N. Abeyasingha, The Radical Tradition, Colombo: Ecumenical Institute, 1985

[vii] Abeyasingha, p. 4

[viii] Aloysius Pieris SJ, An Asian Theology of Liberation, Maryknoll NY: Orbis Books, 1988, p. 81

[ix] Kenneth Fernando, Rediscovering Christ in Asia, New Delhi: ISPCK, 2005

[x] Kenneth Fernando, Through the Year with St John, New Delhi: ISPCK, 2008

[xi] In later years as Bishop of Pretoria he was a pioneering member of both the Anglican-Roman Catholic Joint Preparatory Commission and the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission that started its journey in 1969.

[xii] A term coined by Max Thurian in Priesthood & Ministry: Ecumenical Research, London: Mowbray, 1983, p. 97ff.

[xiii] Kenneth Fernando, ‘Buddhism, Christianity and their Potential for Peace: A Christian Perspective’ in Perry Schmidt-Leukel (Ed.), Buddhism and Christianity in Dialogue: The Gerald Weisfeld Lectures 2004, London: SCM, 2005, p. 233

[xiv] NIFCON had been established in 1993 as a result of Resolution 20 of the Lambeth Conference of 1988.

[xv] https://nifcon.anglicancommunion.org/about-us/history.aspx

[xvi] Abeyasingha, p. 116

[xvii] A term attributed to Isaac Tambyah by John C. England in an article titled Within Our Movements and Histories: The Crane is ever Flying, Asian Christian Review 7.1, 2014. It is based on the The Three-Self Principle (self-governance, self-support or financial independence), and self-propagation or indigenous missionary work that were first defined by Henry Venn, General Secretary of the Church Missionary Society from 1841 to 1873. David Bosch and Paul Hiebert in the 1990s coined the term self-theologising as well.

[xviii] The Bishop’s Charge and Proceedings of the Synod of the Clergy of the Diocese of Colombo, 1966, p. 32

[xix] 1966, p. 33

[xx] Ceylon Churchman 1967

[xxi] Kenneth Fernando, Rediscovering Christ in Asia, New Delhi: ISPCK, 2005, p. 103

[xxii] Fernando, p. 72

[xxiii] Neville Jayaweera, The Role of the Church in the Ethnic Conflict, Colombo: Marga Institute, 2001, p. 10

[xxiv] Jayaweera, 2001, See the list on pages 8 & 9

[xxv] Kenneth Fernando, ‘The Future of our Church’ in Frederick Medis (Ed.) The Church of Ceylon: A History 1945 – 1995, Colombo, 1995, pp. 322 – 323