Addressing God … Guest Editorial

Addressing God

Guest Editorial – post Easter 2023

Michael Collins

Michael Collins, author, lecturer and reviewer, has served as a Reader.

He has worked in the Middle East and Far East. The author of two books he now lives and writes in the Mediterranean area.

It has been well observed that fidelity to tradition must be a creative fidelity. That prompts me as an historian to reflect on what tradition really is and how it comes to be. This question is of fundamental importance to those Anglicans especially who locate themselves in the catholic wing of the Church, since Tradition along with the Bible and Reason, serves as one of the sources of Anglican theology supplementary to Scripture and hence to teaching and practice.

Thus, we must ask what we are being faithful to, and what is its character? To what extent is Tradition a product of history and thus in principle mutable, and to what extent is it a source of revelation independent of the Bible? For many catholic-inclined Anglicans, the Bible indeed, rather than an ahistorical deposit, is itself part of Tradition. Anglicans assert that Tradition cannot be in conflict with Scripture and if it appears to be must be reconciled with Scripture or corrected by Scripture. That position in turn invites the question of what we take Scripture to be because at the root of all these discussions is the human quest for certainty in religion and hence of the locus of authority. Those who wish to safeguard the intellectual and volitional integrity of believers have sometimes rejected Tradition root and branch under the banner of sola scriptura asserting that Scripture contains or witnesses to everything necessary to salvation.

Anglicanism under Modernity, and increasingly as Modernity has fulfilled its logic and challenged and corroded what many have taken as traditional assumptions and beliefs, today risks losing touch with a coherent rationale for Tradition, instead pulling up the anchor supplied by a sense of history and setting out on an uncharted sea. On the way Anglicanism may lose touch with many fellow Christians and its long-cherished atmosphere of eirenic approaches and ecumenical outreach. Independence too stridently asserted and wilfully pursued may lead to isolation, irrelevance and conflict, a sad outcome, potentially damaging to Christianity as a whole, since the Anglican Church for historical reasons has the second-widest reach of any major denomination. Overriding tradition under the Modernist imperative to continual revolution would mean re-conceiving what Anglicanism is and indeed the role of any theistic belief and practice.

By contrast it may be argued that Tradition is indeed historical and by its nature, as a product of engagement with successive societies, a continuing Christian challenge and corrective to the blind spots, inadequacies and false emphases of any particular culture. The role of artificial intelligence, for example, is posing fundamental challenges to our conception of human identity, function, role and worth. Another longstanding challenge, raising issues of freedom and creativity, is the ever-expanding role of the state. Government action, especially when prompted by democratic debate, has played inter aliaan invaluable role in overcoming poverty, inequality, racism and disregard for the rights and dignity of minorities. But does a survey of historical experience not teach us to weigh the price we pay for these advances? Whilst Christianity is inevitably historical, since the incarnation is an event within history, it is not necessarily imprisoned in the past as what has been called ‘British Museum religion’. However great its respect for Tradition, Christianity is not the religion of historians. Rather, Jesus’ metaphors of salt and yeast have much to teach about how the Church should go about engaging with society. Though as catalysts of change both are minority elements, neither risk being absorbed, let alone destroyed as they act.

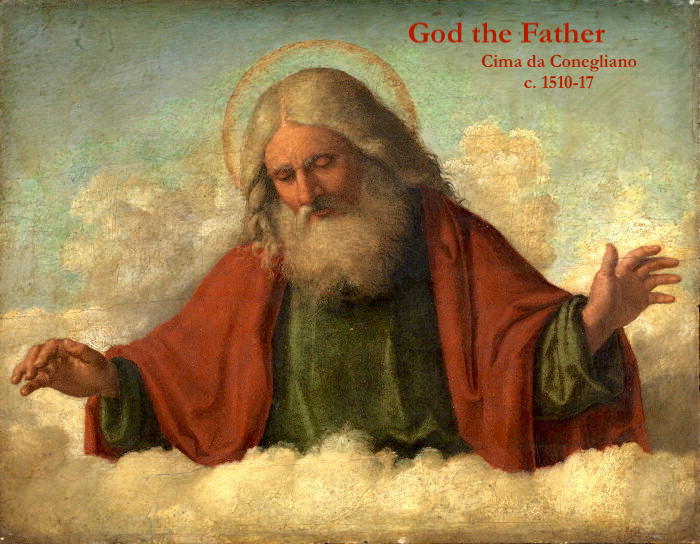

Yet that is precisely the prospect before Anglicanism as it seeks, in and by culture constraint, in time, to commend itself to its cultural environment by adopting items from the surrounding secular culture regardless of what it has traditionally held even if those tenets are apparently drawn from Scripture itself. A prime example currently being bruited is changing the opening invocation of the Lord’s Prayer from ‘Our Father’ to ‘Our Parent’.[i]

The adoption of gender-neutral language prompts us to ask whether, as the Dominical words recorded in scripture, of necessity located in time and constrained by culture, can be modified to suit the priorities and preferences of our own culture? Are these uniquely immune to historical forces, or are they, in some cases at least, liable to change and chance? In other words, why has the value and importance of gender neutrality appeared on the theological agenda after two thousand years? Is it a fundamentally new understanding of the human condition not known to Jesus Himself but arguably inspired by His teaching? Alternatively, is it not so much an advance in understanding and attitudes as a nuanced salve to consciences that have become of secular priorities under the priorities? Changing the way we address God is fundamental and has to be justified and evaluated by prayer, reflection and debate. Making ad hoc changes risks leaving Anglicanism exposed to fad and fashion and, for the sake of some particular advantage losing its identity and integrity.

Michael Collins

Feast of St George 2023

[i] https://theconversation.com/church-of-england-to-explore-gender-neutral-terms-for-god-women-clergys-suggestions-for-replacing-our-father-199541