Review – ENGLISH VICTORIAN CHURCHES: Architecture, Faith, & Revival

by James Stevens Curl

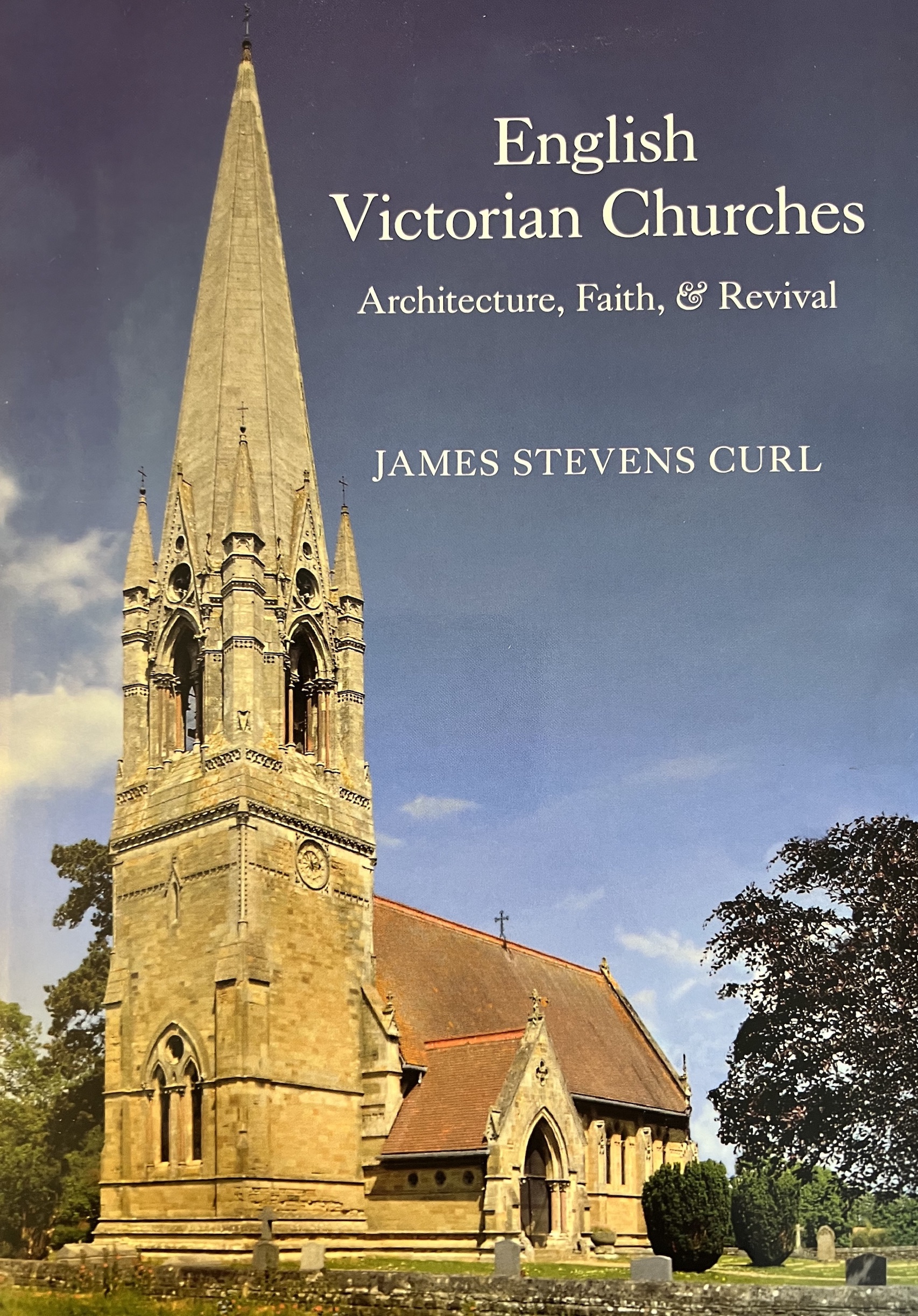

ENGLISH VICTORIAN CHURCHES: Architecture, Faith, & Revival

by James Stevens Curl

REVIEW by John Woodcock

John Woodcock is a conservation Architect practising in London who has worked on the repair of many churches.

Never has this book been so needed!

Over 20 years after the publication of Simon Jenkins’ England’s Thousand Best Churches, this volume again brings to the attention of a wider readership the richness of ecclesiastical architecture. The intervening years have not been kind to our church heritage or indeed the role of the Church as an institution in society generally. As Canon Orford points out in his Preface to Curl’s book, ‘Ignorant zeal has greatly harmed our ecclesiastical inheritance, and, in the 20th and 21st Centuries, Victorian Buildings have been particular targets for misguided adaption and demolition’. However, ‘this book provides the material for preventing such continuing disregard for the surviving fabric entrusted to us’… Absolutely so! Despite over 50 years of campaigning by the Victorian Society and over 60 years dedicated to research and writing on ‘under- appreciated and often threatened Victorian architecture’ by Professor Curl, future generations still stand to regret our lack of appreciation of the extraordinary richness of this heritage. Unfortunately, for the present- day Church hierarchy they are regarded as ‘redundant plant’ to be disposed.

The 1820’s were a period of crisis in English society and in the church following the French Revolutionary wars, with the rise of civil disorder, political radicalism, religious dissent and indeed, low church attendance and popular anti- religious feeling? History has turned full circle it seems and the church is again in crisis but the response of its current leadership could not be more different from that of their Victorian predecessor’s. The Victorians embarked upon the most extraordinary building programme, as well as restoration work on old churches, unprecedented since the last decades of the Middle Ages. Both were periods when England was wealthy, with resources to lavish on the worship of God. Curl highlights the many wealthy individual donors who commissioned some of the finest of these churches, many dedicated to lost loved ones. One such is St Mary the Virgin Clumber Park by G F Bodley, built for the 7th Duke of Newcastle as estate church, but now standing alone in the parkland, his house having been demolished.

Jenkins included 66 Victorian and later churches amongst his 1000 best in England. In this volume James Stevens Curl focuses on the Victorian era, his particular interest and with most emphasis on the architecture of the Catholic revival in the Established (Anglican) church. Curl was Architectural Editor of the Survey of London in the early 1970s and his researches for the Survey volume on North Kensington were the foundation of a life- long interest in Victorian Architecture, particularly churches and cemeteries.

The story which unfolds in Curl’s book could be likened to a mountain walk, with the author as our ‘Wainwright’ leading us. First through a hard slog in the foothills of the first chapters dealing with the early gothic revival and the religious and political crises of the early 19th Century; then as we emerge onto the high ground of the mid- 19thcentury, Curl is in his stride pointing out with enthusiasm the wonderful churches by architects such as Street and Pearson. He relishes the vigour and eclecticism of Burges and later developments under Bodley and the junior Scott’s. This hypothetical walk leads on through further religious crisis at the end of the century, to a flowering in the exquisite work of J N Comper, which continues into the 20th Century. There are fascinating asides on Roman Catholic and Protestant churches and chapels. Ironically, the climax of the journey is perhaps Liverpool Anglican Cathedral by Giles Gilbert Scott and Bodley, not finished until 1978. Then, in the metaphorical pub after our exertions, Curl ruminates over a pint in the last chapter about church restoration and the legacy of George Gilbert ‘Great’ Scott, as well as the future of this heritage.

Curl does not end on an optimistic note unfortunately: ‘such a legacy may, in the end, only be remembered by a few as something that was wonderful, yet was lost’. After this exhilarating journey, the reader should certainly be inspired to visit and appreciate our Victorian heritage and join the campaign for its preservation for future generations.

Beauty is a theme repeatedly high-lighted by Curl, something current generations find difficult to appreciate. He highlights the creative genius and superb craftsmanship which the Victorians poured into their churches, the finest exemplars of which he argues ‘stand comparison with the best mediæval work, often surpassing it in quality.’ Curl challenge’s the continued Ruskinian notion that the 19th century produced only pale mechanical copies of real medieval gothic. He elucidates the imagination and skill of designers as varied as Butterfield, Burges, Pearson and Bodley, as well as the influence of the Arts and Crafts movement and the inventiveness of later generations.

Another strong theme is the rise of the High Church Catholic revival in the Church of England, which aimed at worshiping God in ‘the beauty of holiness’, despite the legal challenges, even in the first years of the 20th Century by the Bishops and Privy Council. In the work of the last exponents of the Gothic revival highly elaborate fittings and decorations create interiors for Eucharistic worship according to a revival of English Mediæval practice, as opposed to Counter Reformation European Roman practices. Curl describes church interiors of great refinement, such as those created by Comper at St Crispin’s, Clarence Gate, London.

Whom is this book intended for? It is a very personal account and one suspects it is for the author himself, wishing to share his great knowledge and enthusiasm. What better reason? However, the problem for academics is that the author has eschewed foot notes and references. For architects it contains no plans of the churches discussed and many buildings described are not illustrated. Why repeat the history of the gothic revival which can be read in Kenneth Clarke or Charles Eastlake’s volumes? There are long explanations of theological arguments, which again retrace familiar territory. If this volume is for the amateur, there is perhaps too much detail on these themes yet not enough basic explanation. For instance, an explanation of the ‘early’ ‘middle’ and ‘ late pointed’ gothic styles, which are referred to constantly, is confined to the excellent Glossary. Some mediæval examples might help. In the same way, if many people have lost connection with any religious understanding, may be a more basic explanation of the Christian faith is required. Why is Communion so central (or not) to worship? Indeed, what IS worship?

Interestingly, Curl emphasises the key role that Oxbridge educated clerics played in spreading the ideas of ecclesiology and an appreciation of mediaeval architecture throughout their parishes. Architects on the other hand he claims tended to followed fashion. He describes the hard work put in by inner city clergy in education and social welfare at a time of great social deprivation.

An explanation of the pivotal role of the practice of George Gilbert ‘Great’ Scott in training successive generations of church architects is largely missing. A reflection of recent scholarship to revaluate his role would have been interesting, although Curl touches on to in his chapter at the end on church restoration. Another theme which is not fully explored is that of the role of the architectural families, including the Scott’s and Pugin’s.

The book includes many beautiful new photographs by the author and the late Geoff Brantwood, amongst others. Yet these are crying out to be full sized folio prints. They focus on the latter part of the story and some of the earlier photographs are poor, for instance of AWN Pugin’s work. The problem is that many churches are mentioned but not illustrated and there can never be enough photographs in a book like this. The author refers to the high costs of reproducing archive illustrations, so compromises presumably had to be made with the publishers to keep the book affordable. May be the fact that the book is a reworking of an earlier volume compiled for English Heritage in 1995, the early chapters and later chapters feel like a different book to the central chapters on the Anglican Revival, where Curl reveals real passion for his subject.

Professor Curl’s book is an impressive volume and an essential read for all those interested in the Victorian era and church architecture. On balance the criticisms may be because of such high expectations from the author’s knowledge and long career. It should be compulsory reading for those training as clergy in any denomination, in the hope that they might appreciate more the design, craftsmanship and, yes, BEAUTY of the wonderful heritage which they have charge of for future generations! Why should the most beautiful buildings which we have not survive dedicated to God?

Lent 2023