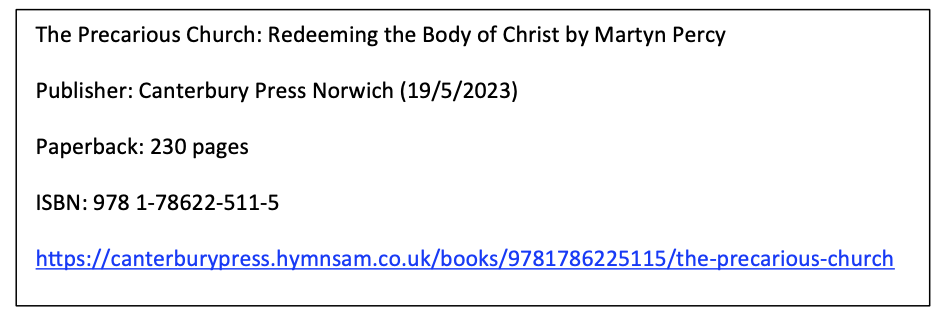

The Precarious Church – Redeeming the Body of Christ

Martyn Percy

Review by Sebastian Satkurunath

Sebastian Satkurunath is a spiritual director and churchwarden in a small North London parish. With a background in mathematics, by day he works as a university data analyst, but is planning to jack it all in and return to the other side of university life as a (very!) mature student, to start a second undergraduate degree in theology.

I wanted to like this book; I really did. The stated premise, that church is at its best when it is outward focused and trusting in God to provide rather than prioritising its own security in the form of financial resources and numerical growth, is a compelling and appealing one, and thoroughly in the spirit of the sermon of the mount (Mt 6.25-34). What’s more, there are clearly many ways in which the Church of England fails to meet this ideal, and I am quite sure that there is a valuable and interesting book to be written about how those failures play out and how we can, as an institution, repent of them, and learn to become more truly the body of Christ on earth. Precarious Church is, sadly, not that book, at least as far as this reader is concerned.

The book is a collection of essays, most of which have been previously published elsewhere, organised into seven sections, each of which concludes with a brief reflection and some discussion questions. There is of course a fine tradition of taking a series of existing essays or sermons and combining them into a book, and there are broadly two ways in which this can be done successfully. One is to own it completely, pick the longest, or your favourite, and call the book something like “In Praise of Idleness and other Essays.” You might write an introduction which draws out a few common themes, but you don’t claim to be making the case for an overarching thesis. Alternatively, you can take a series of essays which all support or contribute to an argument, and you can work them together, filling in the gaps, editing out the more egregious repetitions, until you have something like a coherent whole. The lack of this sort of oversight in this book is made starkly clear by sentences and phrases being repeated in full, in one notable example on consecutive pages.

More serious than this kind of stylistic concern though, is the absence, at least in the first four sections, of much adherence to the purported theme of the book. As far as I could make out, the common thread through these essays had little to do with precarity, so much as a laundry list of the author’s frustrations with the Church of England. Sources of his ire particularly included the bishops, governance, evangelicals, diocesan functions, safeguarding, and the church growth movement. The link from the latter to an abandonment of precarity makes itself, but for the rest, something more explicit was needed, and wasn’t made. Given events of the last few years, it is of course unsurprising that Percy has a great deal of anger towards the church, but that leads to a book in which criticisms that are doubtless fair and justified are tangled up with those which are seen through a distorted lens of personal grievance, and it is very difficult for an outside observer to pick them apart. It is interesting to contrast this sense with the depiction of church given in another ferocious critique, Jarel Robinson-Brown’s ‘Black, Gay, British, Christian, Queer”, where the anger at the institutional failings remains palpable, but there is far more of a sense of appreciation and love of what church gets right.

I must also confess my own biases in one particular aspect of my response. Having worked as a higher education administrator for many years, I have far too often encountered a particular type of academic who complains about all the resources being wasted by central administration but still wants a timetable with no clashes, apparently having the impression that an organisation as large and complex as a university can just magically organise itself. I couldn’t help but see shades of this in Percy’s diatribe against dioceses offering centralised services. Bias notwithstanding, my experience as churchwarden has been that much of the expertise offered by the Diocese of London has been invaluable, and only accessible because our resources were pooled with those of other parishes.

Moving on though, from this negativity, both within the book and in my response to it, the final few chapters mark a turning point, moving on from everything that is wrong in the Church, to offer a vision of what could be, with a far richer set of ideas than we have seen so far. In chapter 16 we are offered the metaphor of cultural climate change, in which the world is changing dramatically, and we cannot respond effectively if we pretend that everything is the same as it always has been. I was particularly struck by the insight that this cultural change is intimately linked to the effects of literal climate change, as resource shortages and changing patterns of migration send shockwaves through our society and world. There is surely much fruit to be found in a further and deeper exploration of this metaphor, and I hope that someone will be inspired to do so.

In chapter 17 we are introduced to the concept of “respair”, meaning “the return of hope after a period of despair”, and I am reminded of much of Walter Bruggemann’s work on the necessity for real and honest lament before it is possible to move on to renewal and re-orientation. And so the book ends on a note of hope. Not, perhaps, hope for the Church of England, but hope for the people of God, doing good, acting kindly, and taking risks to serve one another, and these are some ideas which are well worth encountering and responding to.

If you’re not already concerned about the direction the Church is going, then I doubt this book is going to convince you, so you should probably give it a miss. If you are already concerned, then the first few chapters probably won’t tell you anything new, but if you skip them and jump in at Part 5, and maybe read those final chapters alongside the Robinson-Brown, you may well learn something about how you are being called to work towards redeeming the body of Christ.

Sebastian Satkurunath

August 2023