The Eucharist and the Monomyth

The Eucharist Quest

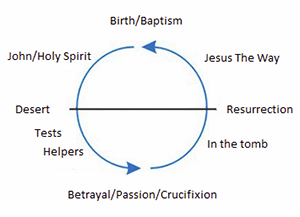

The Hero’s Journey of Christ in Common Worship’s Eucharist Liturgy

Danny Pegg is an ordinand in the Church of England, beginning study at Westcott House, Cambridge in October 2015. He graduated from the University of Kent in 2011 with a 1:1 BAHons in Comparative Literature with Religious Studies. His main theological interests lie within the work of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, liturgy and the overlap between theology and the arts. His dissertation concerned Theology and Cinema and he has since had several theological film reviews published with The Online Journal of Religion and Film.

Danny Pegg is an ordinand in the Church of England, beginning study at Westcott House, Cambridge in October 2015. He graduated from the University of Kent in 2011 with a 1:1 BAHons in Comparative Literature with Religious Studies. His main theological interests lie within the work of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, liturgy and the overlap between theology and the arts. His dissertation concerned Theology and Cinema and he has since had several theological film reviews published with The Online Journal of Religion and Film.

Introduction: The Eucharist and The Monomyth

Why is the Eucharist the central act of worship in many Anglican churches today? It could be said that it is because we feed on Christ in our hearts, minds and spirits and then go forth changed, equipped to live a Christ-like life. We surround the sacrament with readings, singing and ritual action. This combines to form a service of God’s story: we hear about God’s interaction with his people across time in the Old and New Testaments, we hear about Jesus’ earthly ministry and we do what he has asked both in prayer and the sacrament of Holy Communion (and in other elements such as healing or baptism). When we also consider that God speaks to us in our present situation through his Word (scripture and sermon) and imparts his grace in his sacraments here and now, we come to see that we are not simply telling a dead story but being transformed by a living and breathing one.

Joseph Campbell includes the story of Christ in parts of his seminal work The Hero With A Thousand Faces, where he outlines his ‘monomyth’: the one story structure that all fundamental human stories (with some variation in execution and order) conform to. He claims his monomyth is a subconscious human expression of ‘the unconscious desires, fears and tensions that underlie the conscious patterns of human behaviour.’1 In the fictional mythologies from our history we can find an ‘eloquent document of the profoundest depths of the human character’. 2 When humanity reaches out to understand and approach the other, this is the way they tend to do it in narrative form.

Campbell treats Jesus’ narrative as any other myth. As Anglicans who believe the narrative of Jesus (and of God more widely) found in scripture to be true, we are forced to disagree with Campbell’s inclusion of Christ (and other biblical characters). However, if we accept Campbell’s premise in application to fiction: that is, human stories reveal something about the deepest nature of man, it could be that in examining both the structure of Christ’s life on Earth and our own central act of worship that we discover something about the nature of a story that is far beyond just humanity.

In this investigation, the structure of the Eucharist as found in Common Worship will be compared with stages in Jesus’ life and where these might fit into (or vary from) Campbell’s monomyth structure. The aim will be to examine the Eucharist as a journey and to bring its transformational nature to the forefront as it witnesses to, and allows us to partake in, the only true story: God’s story.

Lastly, it is worth saying that whilst there any many views concerning the sacramental (or lack thereof) nature of the Eucharist, it can certainly be said within Anglicanism that the majority of believers would not disagree that in holy communion there is ‘present grace and nourishment for worthy recievers.’3 This investigation is not the place for a discussion of the ‘real presence’ of Christ in the Eucharist. However, it stands against memorialism as a position (as articulated by Huldrych Zwingli et al) in that it affirms that at its most basic, something is happening when we receive the bread and the wine. Beyond that, for the purposes of this investigation, the available distinctions are academic.

The Structure of the Monomyth

‘The mythological hero, setting forth…proceeds, to the threshold of adventure. There he encounters a shadow presence that guards the passage. The hero may…go alive into the kingdom of the dark…or be slain by the opponent and descend in death…Beyond the threshold, then, the hero journeys through a world of unfamiliar yet strangely intimate forces, some of which severely threaten him (tests) some of which give magical aid (helpers). When he arrives at the nadir of the mythological round, he undergoes a supreme ordeal and gains his reward. The triumph may be represented as his recognition by the father-creator (father atonement), his own divinization (apotheosis)… intrinsically it is an expansion of consciousness and therewith of being (illumination, transfiguration, freedom). The final work is that of the return… at the return threshold the transcendental powers must remain behind; the hero re-emerges from the kingdom of dread (return, resurrection). The boon that he brings restores the world (elixir).’4

The above structure is familiar to us all. Be it from The Odyssey, The Epic of Gilgamesh, The Lord of the Rings or Star Wars, we can recognise this narrative pattern. It is not difficult to find elements of the ministry and sacrifice of Christ in the monomyth. If Jesus fitted the pattern ideally, we would perhaps be faced with a serious piece of literary evidence suggesting that Jesus Christ, along with the other heroic figures of the golden age, was merely a product of our own subconscious desires of wish fulfilment. As we shall see, he does not.

It may be more difficult to see in the monomyth our pattern of attending church on a Sunday. However, we believe when we go to church that something happens. We are not merely indulging in a custom like trick-or-treating, that perhaps has a heritage but no ontological significance. We are worshipping God and receiving from him, in the simplest of terms. We can view the liturgy as ‘a path to follow, a mountain to climb, a bridge to cross…and…a setting for an occasion of mystery – the profound mystery of what it is that lies beyond and outside the self.’5

It would be significant therefore if the pattern of the central act of our worship was either similar or conflicting with the archetypal way man expresses himself in his interaction with the other. It would be significant because it could be said that the divine truth at the core of it (the living God) either creates a new structure for itself unlike Campbell’s (as it is truth and not mythology) or else fulfils and makes perfect our human structure of the monomyth (as perhaps the missing ingredient was a true narrative).

Firstly, to what extent the life and death of Jesus fits the monomyth structure needs to be precisely ascertained before proceeding to examine the structure of the Eucharist liturgy as the former is the foundation of the latter.

Then, how the Eucharist liturgy from Common Worship conforms to the pattern of Christ’s life and the monomyth structure itself and what that can do for believers will be considered.

The True Story

The Call to Adventure

According to Campbell, the first stage of the hero’s journey ‘signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual centre of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown.’6 In one sense, we can see this within the beginnings of Jesus’ ministry: the humble carpenter comes forth as the messiah at the ordained time. He goes from civilian life, to life as a wandering prophet. However there are several elements that do not align Jesus with the heroes of antiquity.

Firstly, he is not called. Whilst we could argue that God sends him forth to the desert at the right moment, we do not think of Jesus as just a man before his ministry and then a man given a destiny after his baptism. Jesus is the Word that was with God in the beginning. In unity with the Father and the Spirit, Jesus is his own centre of action: there are no outside forces at work. Why Jesus’ ministry begun when it did is simply through his beginning of it and nothing else.

In thinking of Jesus as the Word, who was made flesh and dwelt among us, we are presented with another difficulty. Jesus’ ‘quest’ is to our world; the normal, material, human world. He is not called away to the distant lands or the magical forest. Jesus had (and has) work to do here. He comes from heaven (the ‘realm of the gods’ in literary terms) to Earth: his ‘zone unknown’ is here.

For Jesus’ ‘call’ then we could reach all the way back to the birth narratives in the gospels. His sending here could be seen as his beginning. God’s intention in sending the Son was that he may live a truly human life: birth, temptation, tiredness, joy, death. In coming to Earth, he redeems it. Jesus’ purpose was prefigured in the messianic prophecies and the life he would live was told to Mary by Gabriel: in this sense, Jesus, as hero-figure, was always called. In this we again have a reversal of the expected: Jesus does not have a ‘call to adventure’ so much as he himself is the catalyst of the ‘adventure’.

Instead of coming from within the world and going beyond for salvation, Jesus comes into the world to bring salvation; instead of being chosen for a purpose, Jesus was always the solution.

The Helper

Before the hero crosses the first threshold and truly begins the adventure, he is met by a person who can help him against the ‘dragon forces’ protecting the way forward.7 Before Jesus can begin his ministry, he seeks out John the Baptist. John is the herald of Jesus, he has been ‘the voice of one calling in the desert’.8 He knows that one greater than himself is coming and is keen to emphasise he is not the messiah. Jesus comes to be baptised before he begins his earthly ministry. However, this baptism is not like the protection given by other helper-figures.

Unlike the gods equipping the Greek heroes, John is not superior to Jesus in any way. He initially refuses to baptise Jesus because he cannot be worthy to do so. When he finally does, it is the Holy Spirit descending upon him that appears to be the true ‘helper’. The ‘endorsement from God’9 is what is needed, not supernatural aid from an agent of the world.

John the Baptist does fit the role of helper in that he is the eclectic wise figure who is not in the city among the masses, he is apart from the world, preaching and teaching in the desert, clothed in animal skins. Whilst he is not unlike Campbell’s ‘little fellow of the wood’10, we have an inversion of a usual aspect in the monomyth again. Instead of the wise-man figure bestowing great power on the lesser hero for the task he cannot complete himself, we have the self-proclaimed lesser person doing all he can do (signposting) for Jesus who is yet again the initiator of action here. The Holy Spirit descending on Jesus affirms his identity and purpose to the world (but does not grant Jesus supernatural aid as per the monomyth) so that with the way made ready, he can cross the threshold into his ministry.

Crossing the Threshold

Immediately after being baptised, Jesus withdraws to the desert for forty days and forty nights where he is tempted. Before he can fully enter the world in ministry, he is tempted by Satan, the dragon of the bible. Jesus is tempted to use the power and authority that he has been given as the Son of God for his own means instead of for the purpose of the Father.

Campbell notes that this threshold guardian is one of the ‘dangerous presences every desert place outside of the normal traffic of the village’11 has. Just as Eve was tempted by the snake and fell, so must the Son of God in his truly human existence be subject to this temptation also. The shadow presence is the vision of himself that Satan presents Jesus with: each of his temptations are mirrors to Jesus’ true path, the worst versions of what could happen if his power and authority was used selfishly.

But unlike Cerberus at the gates of Hades, the guardian is not a powerful enemy that must be overcome but rather a lesser-being whose only potential success lies in Jesus himself being the agent of action once again and choosing unwisely. This is not the say that this is not a challenge for Jesus: if his truly human life is to be of worth then it cannot be a mere charade, indeed after Satan is finished the ‘angels came and attended him’12 indicating that it has been an ordeal. However, Jesus still has the upper hand because with inaction he has succeeded unlike a battle he must win with cunning or brawn. The serpent seeks a dominion over Jesus that he does not already have.

Also, as Jesus’ journey is to the world and not to the faraway land through the desert-place, Jesus is wilfully subjecting himself to this trial. His ministry is among the people and the desert in which he is tempted is not on the route to the city. The dark forces that usually plague a hero’s journey do not have the same place in Jesus’ story: they appear to only get to exert any presence or influence when he allows them to.13 Satan does not succeed in tempting Jesus and so his ministry begins: Jesus is not leaving the path that he set out on.

In his humanity, he is subject to the world yet in his divinity, he is beyond the world. Jesus’ redemption of humanity through participating fully in being made flesh is key to the comparison of the monomyth with Jesus’ life and death and therefore key to how our humanity can participate in his divinity through worship. This shall be returned to later in the investigation.

Tests and Helpers on The Road of Trials

The Road of Trials is what Campbell calls ‘the long and really perilous path of initiatory conquests and moments of illumination’.14 This is Odysseus encountering the sirens, Polyphemos and the Opium-Eaters; this is the trials of Hercules; this is Dante journeying through the various levels of Hell. In terms of the life of Jesus, his ministry before the Triumphal Entry when he knows his death approaches, is his Road of Trials.

It does not appear difficult to describe Jesus’ ministry as one full of tests. He encounters people possessed by demonic spirits, disbelief and misunderstanding among his own followers and others, and he is confronted by the religious leaders of the Jews at every turn. We witness Jesus losing his temper and him being threatened. It is not a meek and mild journey of unabashed happiness.

However there is no time when Jesus completely cannot do what he sets out to do. When he is faced with a lack of belief in his home town, Jesus still manages to heal. When people fall away, the twelve do not. When he sets out to speak and teach, he does, even if he is forced to leave. Jesus cannot be muzzled by any human authority.15 He succeeds in his ministry and when he is faced with actual threat such as being seized or attacked, he always manages to slip away and evade his captors because, we are told, ‘his hour had not yet come’.16 This is not a deux ex machina: what Jesus has come to do, he will do. He is not conveniently saved at every turn by a supernatural guardian, rather he is again the agent of his own path in doing the will of the Father that sent him, endorsed by the Spirit. How people react to his message and follow his teachings is fully in their hands (we read that some follow and some do not) but Jesus’ ministry and ultimate salvific sacrifice are not optional events, occurring by chance.

Campbell calls the victories along the way ‘momentary glimpses of the wonderful land.’17 The hero receives a prize for slaying a beast or overcoming a puzzle and he is given a hint or foretaste of the ultimate goal of his journey: the hero’s success points to the final success. Jesus’ miracles are referred to as signs in the fourth gospel: signs that point to the glory of the kingdom of God and give a foretaste of it. As we read in the summary of the monomyth above, the ultimate boon of the hero is brought back whilst the land beyond and the ‘transcendental powers’ are left behind. However, in being the one true sacrifice for sin and in opening the way to salvation for us, Jesus does not merely secure a boon of the Kingdom for us, but the entire Kingdom itself as Jesus has come to tell us that the Kingdom is within us.18 Jesus then does not face tests or overcome them in the usual way of the monomyth.

If Jesus is the agent of his own path then and is not tested in the usual way, is he helped on his journey in the usual way? Jesus often departs from his disciples alone to pray: it could be said that God the Father is Jesus’ primary helper in his ministry. It is more difficult to see the twelve as helpers when they are so often a source of frustration for Jesus. However, arguably they help him practically (through the crowds, buying food), offer fellowship and are his hand-picked community. He professes his love for them clearly and they do the same for him. It cannot be denied that Jesus has a plethora of meaningful human relationships, but it does not seem that Jesus has helpers in the same way that the classical heroes are aided by people with skills (or magic, or knowledge) beyond his own.

There is one person in his life on whose action Jesus appears to depend: Judas.19 Judas’ actions are known by Jesus, indeed he reveals his knowledge of his betrayer at the Last Supper. Jesus knows Judas’ betrayal is necessary. Whilst it may be distasteful to speak of his betrayal as ‘help’, it is the only human action that Jesus appears to need: everything else in his ministry has been at his insistence and through his ability. Again we are faced with an inversion of the expected when we examine Jesus’ life alongside the monomyth structure.

It should also be noted that the only moment since the temptations that Satan moves against Jesus is noted in Luke, where he possesses Judas. The only time the ‘dragon forces’ have any power is within the full knowledge and submission of Jesus Christ.

The Supreme Ordeal

The supreme ordeal is the final battle between good and evil: the conflict that the journey has always been heading toward. The categories of supreme ordeal that appear to apply to Jesus in Campbell’s structure are ‘Atonement with the Father’ and ‘Apotheosis’.

Starting with atonement, Campbell here is thinking of the demi-gods such as Hercules being forgiven and being redeemed by their wrathful father-gods such as Zeus. Luke Skywalker coming to peace with his fallen father, Darth Vader, would fall into the same category. However, Jesus himself needs no atonement and no matter which atonement theory is applied, God the Father is not the enemy in this journey.

In dying for us (whether that be to pay a debt, to be our substitute, and/or to re/open the way to salvation) Jesus’ purpose is purely for us: he is totally selfless and earns nothing from his journey that is only for himself. Jesus also is not being united with the Father as a goal, but returning to the Father after his work his done.

Campbell outlines the usual Son/Father motif as a situation in which the Son is united with the Father truly for the first time and that because of that, this world is changed: ‘For the Son… the world is longer a vale of tears but a bliss-yielding, perpetual manifestation of the Presence.’20 But Jesus has never been in disunity with the Father and the change in the world is for all of us not for himself. The Messiah is not another prophet given the toughest challenge, leading the battle; the Messiah is God himself made flesh acting completely selflessly.

In apotheosis, Campbell is referring to heroes who achieve divinity for themselves. They are those who through their ordeals break the bonds of mere humanity and ascend to the ranks of gods themselves. Without getting ahead of ourselves, Jesus’ resurrection and ascension appears to fit this model from a purely narrative point of view. However as we know, Jesus needs to attain no divinity as he is the one through which all was created in the beginning. In the narrative of Jesus’ life and supreme ordeal of arrest, torture and death, we are presented with what could be called a deapotheosis. In Jesus, God lowers himself, empties himself, is made man and receives an experience of the worst of humanity, dying himself in the most painful and humiliating way. Jesus Christ has the ultimate Campbellian Supreme Ordeal throughout which he surrenders himself to the will of the Father. Jesus’ supreme ordeal surpasses and yet reverses the expected in the monomyth.

If this victory seems at all devalued by the pre-ordination of its happening, we only have to look to the agony in the garden to find reassertion of Jesus’ full humanity. This tells us that the narrative is not simply one of an irresistible force cleaving through our experience on a pre-destined path but actually is God being fully made man, with all the danger and vulnerability that comes with that: ‘Father if you are willing, take this cup from me.’21 At the very least, his prayer ‘suggests hesitation about the future’ if not sharing ‘in the human condition of of being uncertain about God.’ 22 Whilst the mystery of the incarnation elevates Jesus and lowers him at the same time, we can be sure that by participating in our humanity fully, Jesus truly did undergo an ordeal in his passion.

The Flight

With the supreme ordeal over, the hero needs to flee back to the threshold to return to the world with the boon his actions have secured. In this element of the monomyth, Jesus could not be more antithetical. Jesus does not succeed in his ordeal and thus avoid the punishment; Jesus succeeds in being punished. He does not narrowly escape death but rather conquers death and sin. The threshold to his world is not a geographical location. Jesus simply has no flight from his ordeal: his body lay in the tomb for three days. The boon he has secured is for the world, he does not take his victory away to heaven. There is nothing in the world that could chase him back to heaven even if he were not dead, Jesus will go when it is the time to go by his own volition. Again, he is the agent of action in his journey.

Tradition however may provide a flight for Jesus. Tradition provides us with the harrowing of hell: Jesus’ descent into hell and redemption of the dead therein before his resurrection. This is very familiar territory when it comes to the monomyth: we have the Orpheus archetype of travellers into the underworld to save a lost soul and return to the world of the living. The fact that it is so familiar to the usual structure of the monomyth and that we have no evidence for this in scripture lends credo to the idea that this is mythology. It is a story like the apocryphal youth narratives of Christ, that are examples of man trying to explain something about God that he does not know. The harrowing of hell highlights just how dissimilar Jesus’ life and death have been at every point of the monomyth structure.

The Return and The Elixir

‘The two worlds, the divine and the human, can be pictured only as distinct from each other… The hero adventures out of the land we know into darkness…and his return is described as a coming back out of that yonder zone. Nevertheless… the two kingdoms are actually one. The realm of the gods is a forgotten dimension of the world we know.’23

In the myths and legends of old the heroes can always get to where they are supposed never to be able to. But, the disciples are told ‘Where I am going, you cannot follow now.’24 We cannot overcome death as Jesus did here on Earth. Jesus does not go out from here to a distant land; he comes from the Father in heaven and returns to him. Campbell’s depiction of the realms of myth as universal places in the human psyche is completely inverted in the truth of Christ; this story is not of human origin. This is ‘the fundamental drama of all human existence’25: in it heaven and Earth are made one in the Kingdom of God drawing near, made accessible by Jesus, the Word made flesh. His is not a story among stories and he does not fit our moulds.

Jesus is resurrected. He commissions the disciples and ascends to heaven. Yet, he is not gone, he is with us until the end.26 The Holy Spirit is sent to equip the disciples and be with us forever.27 Jesus as the way, the truth and the life is himself the boon. This boon does not run out nor is it a change of one element of the world. Through Jesus, all transformation is possible. Through him we can defeat sin, live as we are supposed to, work as his hands and his feet in this world, help bring about the Kingdom on Earth and live eternally with God in heaven.

The Elixir is not the fire from the gods, stolen for our personal advancement. We only advance and achieve in him, not as agents of our own destiny. We are made in his image and we share in the royal inheritance of Christ, by his sacrifice and love. The boon-gift for the world, is truly for the world and is not about us being better humans in our own right. After all, the last shall be first, the meek shall inherit the earth and those who want to lead must serve. Jesus reverses all human expectation in line with the perfect divine plan.

In the messiah, the Jewish people were expecting a king in the line of David, who would free them from oppression. Instead they were presented with the carpenter from Nazareth who claimed to be the Son of God himself. The monomyth is the archetypal human story from which our greatest fears and desires can be discerned and from which re-enacting, reflecting psychoanalytically and ritually engaging, personal transformation can be achieved. Jesus inverts and supersedes this structure in his time on earth and beyond and in doing so grants us access to a divine transformation that can in turn transform the entire world. As the Jews were wrong about the messiah, so we in our mythic exploration were completely wrong about the hero. In fiction, we can save ourselves but in reality Christ saves the world. Examined in the light of the monomyth, Jesus Christ fulfils all of humanity’s hopes and wishes to a perfect degree in a way that nothing human ever could.

But the story is not over. We believe that whilst Jesus’ entrance into history at a unique time and place was a once-for-all event, the work and will of God continues now for us in living his word and worshipping him for he is the living God, beyond time and space. He is ‘who is and who was, and who is to come’.28 His will, his very self and his transforming love are still available to us now and one of the most important ways we approach him is in worship.

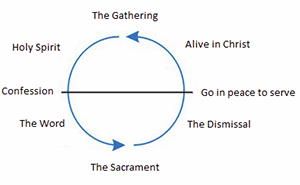

The Eucharist as the central act of Anglican worship, is how we experience God’s story and meet with him time and again. This investigation suggests that the Eucharist could be in itself a journey for believers as it contributes to ‘the story of our relationship to God and one another’.29 In examining it alongside the monomyth and Jesus’ own journey, the potential of the entire liturgy as opposed to only the nature of sacrament at the heart of it shall be considered.

Our Story

It is fair to assert that the majority of worshippers at any given Eucharist on any given Sunday are not approaching the service in the mindset of a hero on a quest. That is not the claim here, but rather that through the living God who the liturgy attests to, we are able to share in his story and be changed by it ourselves.

It could be said that in attempting to appropriate the monomyth structure for an examination of the liturgy, that a merely human structure is being applied to a human ritual: that we are taking a step back from the conclusion of inversion and fulfilment above. However, in continuing the institution of Christ himself in the sacrament and approaching God in the best way we know how to, in praise, recitation of scripture, preaching, prayer and confession (in line with biblical example and tradition of 1800+ years30) it could be said that we are on some level using humanity’s oldest, personal, revealing shout into the void to now approach the truth: the living God. Now that the object of approach is a true one, the monomyth is vindicated, inverted and amplified: God makes perfect our imperfect attempt and communicates his grace and love through it, transforming us.

As the bleeding woman in the gospels reaches out for Jesus’ robe knowing she will be healed, no doubt knowing full well that there was nothing innately special about his clothing, so we in liturgy reach out in worship knowing that only through God are our words and actions, churches and altars, bread and wine made holy.

The Call to Adventure

If Jesus’ life was the ultimate example and yet inversion of the monomyth, then it would not be unreasonable to assume that as it is God that is the electricity to our liturgical machine, that we find a similar pattern in an examination of the structure alongside the liturgy. However, now we are examining the journey for believers, for humans as opposed to Jesus, we may find unity with the monomyth structure in places we did not above.

In terms of a transferral of our spiritual gravity from our every day lives to a ‘zone unknown’, attending a Eucharist appears to be precisely that: we travel from our homes to a (sometimes) ancient building for an ancient and yet current purpose. The congregation gathers to worship, leaving behind the everyday. The first section of the Eucharist liturgy in Common Worship is called the Gathering. It is not something that can be done alone; a priest cannot celebrate the liturgy on his own. Immediately then, we are not journeying alone as the Campbellian hero does. The rest of the congregation are not our crew or teammates on an adventure but rather individuals seeking communion with their God, in community as instructed: ‘For where two or three gather in my name…’31

We can see the call to worship in the church bells ringing out across the land, but the true call for all believers is Jesus Christ himself: come, be with each other and be with me, be forgiven, feed on me in Word and Sacrament. He is the one who said he would draw all people to himself. He draws the congregation together, he draws them into a community who love and strengthen each other. The Gathering then is the ‘springboard, from which the worshipper is put into a proper frame of hearts and mind and launched into the dimension of the domain of God…In the experience of gathering, the individual finds recognition, identity and mutual love.’32

It remains a call for us though, because we are invited. We are not forced. We are invited to come into his presence and leave our material concerns behind and participate in ‘an interpretation of our lives on the basis of faith in Jesus Christ’33 but we do not have to. The journey is there for us to take if only we will take the first steps. The pilgrimage of our lives in Christ is one of faith and choosing to believe and love, not an irresistible fate concocted by an egotistical demiurge: so too, is the Eucharist.

The Helper

For Jesus, no human helper was enough for him to begin his ministry, for him to reach us. Similarly, in order for us to reach him we need divine assistance. The ‘help’ we are given at the beginning of our Christian pilgrimage is our baptism: God sets us apart as one of his own and the Holy Spirit descends on us as it did at Jesus’ baptism.

The Gathering section of the liturgy reminds us that we are his community, the baptised. The baptismal waters that welcome us into God’s forgiveness are waters that we revisit when we sign ourselves with holy water and when we are splashed at another’s baptism. Similarly, before we hear his Word and receive him in his Sacrament, we need to be revisit the assurance of God’s forgiveness and love in order to help us step out of our every day lives to participate in the liturgy that attests to what was, what is and what is to come. It is not a surprise then that the liturgy starts with the Greeting (we are welcomed as the people of God) followed by the Prayer of Preparation which calls down the Holy Spirit and asks for the cleansing of our hearts once more so that we can truly worship.

The only help we need is made starkly clear in the Psalmist’s cry: ‘From where shall my help come? My help comes from the Lord, who made heaven and earth’.34

Crossing the Threshold

Jesus’ life was without sin, but by partaking in our humanity he struggled with temptation in the desert before he could cross the threshold and begin his ministry. We are not without sin and so before crossing the threshold and meeting with God we must acknowledge our sin as individuals and as community and ask for forgiveness. Jesus has promised forgiveness but it must be sought.

The two supplied Prayers of Penitence in the Order One Eucharist liturgy within Common Worship contain the phrases: ‘Forgive us all that is past and grant that we may serve you in newness of life’ and ‘help us to amend what we are, and direct what we shall be; that we may do justly’. These prayers highlight sin as the ‘dragon force’ that always plagues our pathways: it is a barrier to living life as God wills us and thus serving as we should.

But as with the Helper above, we cannot do things apart from Jesus. The president gives us assurance of our forgiveness exercising the authority of the Church given to it by Jesus Christ, praying for us and (sometimes) making the sign of the cross over us in blessing. Jesus then is the agent of action in our journey too: we are only able to cross this threshold (and all thresholds in our journey) because he has opened the way and continues to be with us on it, assuring us of his promises and granting us the gifts only he can give.

However, because Jesus is the agent of action does not mean that we are purely passive, but rather we must respond to his action and story. As with the call that we must answer, we must seriously and genuinely ask for forgiveness to receive it. In a time when fresh expressions of ministry and worship are causing questioning of traditional liturgy, we must not under emphasise the ontological significance of what is happening during the various parts of the liturgy. Nothing is being done for the sake of doing it, but rather all of it occurs with symbol and purpose. We must not take these acts lightly, because if we do we inevitably only receive what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called ‘cheap grace’; a grace that ‘is not the kind of forgiveness of sin which frees us from the toils of sin’35 and miss out on the life-changing grace that our God truly offers.

If we are to truly cross the threshold, be vulnerable and open to receive from God then we have to acknowledge ourselves as sinners and ask for the forgiveness that Jesus has won for us in faith. If we do not think of ourselves as sinners, then we need not continue on in the journey, for to deny our need of his forgiveness, denies all need for him whatsoever. In recognising our need and the love he has for us, we join with the angels in the song of everlasting praise and sing the Gloria as we enter the ‘zone unknown’; the place in which ‘seeing the future in the context of the past has a transforming effect upon the present’.36

Tests and Helpers on the Road of Trials

Describing The Liturgy of the Word (readings, sermon, prayers) as a road of trials may not seem appropriate. It truly is a road though because here we walk through scripture from anywhere between the beginning and the end. We walk through creation, the prophets, Jesus’ life, the apostles ministry and the end times. We are confronted with the lows of the psalmist and the ecstasy of the apostles. Having the scriptures read and hearing a sermon or homily is not the church equivalent of story time. We believe that God speaks to us now through his Word as read from scripture and proclaimed in preaching. Therefore, we must listen and consider in our hearts what God is saying to us as a person, as a church community and as humanity in the world today.

In the worshippers journey in the Eucharist here are our tests and helpers: the parts of the Word that call on us to change and the parts that affirm and encourage us. Through the Liturgy of the Word we hear about God’s relationship to humanity in the past, the culmination of God’s plan in the future and the love God has for us in the here and now. Before and after the readings and sermon we show our thankfulness and glorify God in song and prayer. We know that Jesus goes before us and where we struggle with following him, he is there and where we rejoice in him, he rejoices. ‘The Road of Trials then is not something we have to face alone. We struggle and rejoice: in hearing, learning from and living the Word, we pick up our cross and we bear it, knowing that in him, somehow, the burden is light.

The Supreme Ordeal

‘In the Eucharist we celebrate not only Jesus’ incarnation but his death and resurrection, the culminating points of his incarnation. Even the dark abysses of death are transformed by Christ. Even in death we cannot be separated from union with God. By representing the mysteries of Jesus’ incarnation and of his death and resurrection, the church enables us to share in them. Then we are received into the mystery of the way Jesus followed, which leads us to union with God. It also assures us that we can no longer be separated from Christ’s love’.’37

Receiving the body and blood of Jesus Christ in the sacrament and all that we find in it is not in itself an ordeal. It is a great gift from God; a means of communion with him and a vessel for his grace. But encountering God, feeling his presence and receiving his grace can change us. In coming forward in vulnerability and love, to meet with our Lord is a powerful thing. Undergoing transformation in being received into his mystery is a leap of faith: we have to trust in God and allow him into our hearts. To our modern society, this can be seen as a dangerous sentiment. The Eucharist can…

‘…actually change individual experience, and consequently affect human society at a fundamental level, by encouraging changes in the way we think about ourselves and the roles we are prepared to play among our fellow women and men – either by breaking new ground or preserving sources of nourishment threatened by destructive social change. The action of the rite is to invoke a more powerful presence than the dominant social structure…threatening the status quo…This is necessary anarchy.’38

Are we brave enough to follow God’s will in all things? Are we willing to follow his way even when he says himself it will not be easy? In our contemporary context, can we proclaim the gospel unashamed and uninhibited? The ordeal we find in the Eucharist is this: are we willing to let go of our sin and have true communion with God, listening for him and doing of us what he asks.

We are confronted with the option of partaking in and living out the reward Christ won for us on the cross. The liturgy reminds us of the last supper, the crucifixion and the resurrection in its words. We reconstruct the supreme ordeal of Jesus’ life because from his death comes new life, for us all. He died that we might live. The liturgy allows us to partake in these moments: our potential future, both here as the hands and feet of Christ in the world and our ultimate future in heaven, in the light of Jesus’ sacrifice for us on the cross and the opening of the way to salvation brings about transformation in us, if we let it.

Because of Jesus’, the heart of our journey is not to win something or receive a bounty. A gift is offered and is always offered; the battle has taken place before we come to the table. In the monomyth, eternal life, union with God and changing the world are all very common boons to be won after a supreme ordeal but Jesus’ power was in his powerlessness39; he inverted the expectation, he experienced human suffering in its fullness and conquered death and sin in doing so. We join with God, receive eternal life and go out in the world changed and ready to change because he loves us and we love him. We empty ourselves, laying our lives before him and he comes to us having emptied himself: our ‘hero’ has gone before us and now invites us to join him in victory. He has suffered for our transgressions and because of that, whilst there may be challenge, there is no Supreme Ordeal for us to face on this journey.

The Flight

From the open table there is nothing to flee, but we must return to our seats. We cannot remain here, kneeling, receiving, permanently. Jesus has promised to walk with us in all we do and we must return to the everyday having received from him, met with him and being changed by him to live out his gospel in the world as he asks us to.

Instead of fleeing from the disturbed beasts or being magically aided back to the realm of normality, carrying with us the trophy of the quest, we are compassionately sent back to our lives, thanking God (post-communion prayer) and transformed carrying inside of ourselves as a result of our communion with him, the light of Christ which we are lovingly compelled to share in an overflowing of the living water that rises within us. We are made vessels of the boon, that is, through us Christ can work in the world. We do not bring back a thing that changes the world, we are changed and share that with the world.

The Dismissal speaks this plainly when it bids us to ‘go in peace to love and serve the Lord.’ Once again we are confronted with speaking of our future in the context of our shared past changing the present: God effects change in us now through his love and grace by bringing the future and past of his people to bear on each other in the timeless space that is born in liturgy.

The Return and The Elixir

Our return only happens once we leave our worshipping community and building behind. Earlier in this investigation it was claimed that the Eucharist contributes to ‘the story of our relationship to God and one another’. It is not the entirety of that story because our relationship both to God and others is of course not restricted to liturgical time and place. It could be said though that it is the forge in which by his Word and Sacrament we are transformed time and again, in ways large and small, into the likeness of the person we can be in Christ Jesus. We return to our daily lives, our souls sated by the divine meal of living word, body and blood and yet we are never alone in our elixir-transformed world because we are loved by a personal God who enters into a relationship with us and brings about his world-changing through us. We are given the supreme gift and we help to give it. We love and we are loved.

We return because Christ calls us to, as he too called us to begin our journey. Christ is always the one that calls because he has gone before us. We are able as fallible sinning beings to go back to God each time with our lives in our hands, love in our hearts and apology and thanks on our lips knowing that in his infinite love, humanity being reconciled to him in Jesus, he will embrace us as the father embraced the prodigal son. We were dead and now we are alive, in him who was dead and now is alive forever.

We are able to walk on the journey, encounter, trust, receive, return and share what we have received only through him. We cannot rely solely on ourselves, on our gifts, strength or wisdom, unlike the heroes of old but we do not journey alone and nor do we attempt to win glory for ourselves. We are not heroes on this journey: we are disciples.

Conclusion: The Eucharist Quest

This investigation’s aim was to bring the transformational nature of the Eucharist to the forefront in examining the life and death of Jesus Christ and the liturgy of the Eucharist in light of Joseph Campbell’s monomyth structure. Jesus’ story and thus our story does not fit neatly into the structure but rather it inverts and subverts it and in doing so perfects it. The one true world redeemer is not one of us but rather the one through whom we were all made: God was made flesh in his love for us and gave freely of his life that we might be saved. He comes from without, not within; he comes to us, he does not go beyond; he gives all he has freely, he does not win us a prize. His story is the true story that gives our life meaning and purpose. Jesus’ ‘hero’s journey’ thwarts our expectations at every turn and yet meets our every need beyond all the ways we could have dreamed of. In discussing heroes and saints (in the New Testament sense meaning one of God’s people) Samuel Wells says:

‘…stories are told with the heroes at the centre of them and the stories are told to laud the values of the hero – for if the hero failed, all would be lost. By contrast a saint can fail in a way that a hero can’t, because the failure of a saint reveals the forgiveness and the new possibilities made in God, and the saint is just a small character in a story that’s always fundamentally about God.’40

The heart of our story is Jesus. The heart of Jesus story is the cross. The sacrificial act at the nexus of earthly time and space reaches backwards and forwards in time and gives all else meaning. Because both the ‘story and rite move inwards toward the centre before moving outwards toward an expression and declaration of new life’41 so our journey can be made in the new life given from his ultimate journey. The Eucharist, in attesting to the truth of our existence, offers us a way to regularly connect and reconnect our story to Jesus’ and to experience the transformation that can only come from the ‘costly grace’, given to us freely and paid for by the ultimate price, offered in love and taken if we are but willing to embark on the journey.

1 Campbell, Joseph; The Hero With A Thousand Faces; Fontana Press, 1993: p.256

2 Ibid.

3 Crockett, William R; ‘Holy Communion’ in The Study of Anglicanism, The Cromwell Press, 1995: p.278 4 Campbell, Joseph; Ibid. p245f.

5 Grainger, Roger; The Drama of the Rite; Sussex Academic Press, 2009: p.3

6 Campbell, Joseph; Ibid. p.58

7 Ibid. p.69

8 John 1:23 NIV

9 McGrath, Alistair; NIV Bible Commentary, Hodder and Stoughton, 1996: p.238

10 Campbell, Joseph; Ibid. p.72

11 Ibid. p.78

12 Matt. 4:11 NIV

13 Although we find in Luke 4:13 the ominous note of Satan leaving Jesus until ‘an opportune time’, even then Satan only acts within the realms of Jesus’ knowledge (Judas, etc).

14 Ibid. p.109

15 It may be said that Jesus’ crucifixion and Judas’ betrayal are failures, if not theologically speaking then at least narratively. However, whilst this paper is not the place for a debate of how much Jesus is aware of at any one time of his future, the two aforementioned events are clearly known to him before they take place, solidifying them as events that he allowed to occur.

16 John 7:30 NIV

17 Ibid.

18 Luke 17:21 NIV

19 There is not space in this investigation to discuss fully the many interpretations of Judas’ actions and what the Christological ramifications of those actions are. For this investigation, it is only asserted that Judas’ actions were his own and they were known about to Jesus ahead of the moment, as per the scriptural account. It may be that this could be considered a failure for Jesus (‘and no-one will snatch them out of my hand’ John 10:29b NIV) or that perhaps Judas should not be considered guilty for his seemingly necessary actions. For more investigation in this area, see Cane, Anthony; The Place of Judas Iscariot in Christology, Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2005 or similar.

20 Ibid. p. 148

21 Luke 22:42 NIV

22 McGrath, Alistair; Ibid. p. 282

23 Campbell, Joseph; Ibid. p. 217

24 John 13:36 NIV

25 Radcliffe, Timothy; Why Go To Church? The Drama of the Eucharist, Continuum Books, 2008: p. 7

26 Matthew 28:20 NIV

27 John 14:16 NIV

28 Revelation 1:8 NIV

29 Grainger, Roger; Ibid. p. 1

30 Noting the similarities of Justin Martyr’s description of a service at approx AD 150 in I Apology 67.

31 Matthew 18:20 NIV

32 Giles, Richard; ‘Gathering’ in Renewing the Eucharist: Journey, Canterbury Press, 2008: p. 19

33 Grun, Anselm; The Seven Sacraments, Continuum, 2003: p. 47

34 Psalm 121: 1b-2 NIV

35 Bonhoeffer, Dietrich; The Cost of Discipleship, SCM Press, 1962: p. 36

36 Grainger, Roger; Ibid. p. 5

37 Grun, Anselm; Ibid. p. 62

38 Grainger, Roger; Ibid. p. 76f

39 Radcliffe, Timothy; Ibid. p. 132

40 Wells, Samuel; ‘Theological Ethics’ in God’s Advocates: Christian Thinkers in Conversation, London, 2005: p. 180

41 Grainger, Roger; Ibid. p. 36