The rise and rise of autocracy

The rise and rise of autocracy

Editorial

Pentecost 2023

The Rev’d Dr. Nicholas Henderson – Editor

Democracy is the de jure status of the world with only Saudi Arabia, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Brunei, Afghanistan and the Vatican not claiming that system.

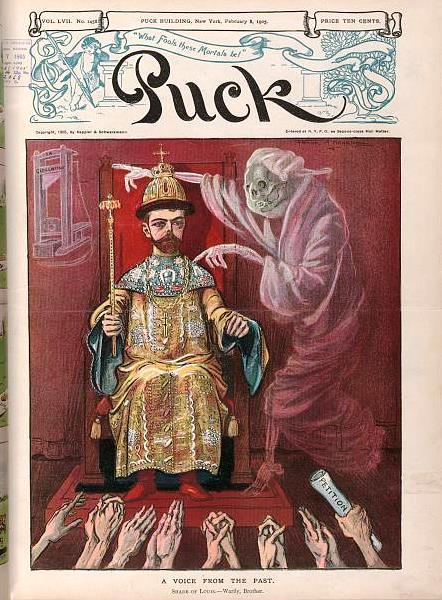

The question must therefore arise as to what democracy really is? Increasingly, with a tightening of centralised state control, bringing the judiciary under governmental oversight and electoral manipulation, democracy appears more like a veneer of legitimisation for what are otherwise autocracies. We might initially cite as examples former communist states such as China or Russia but more worrying are countries such as Turkey, or even in the European Union, Hungary and Poland where the drift towards autocracy is growing.[i]

The term democracy is from the ancient Greek δημοκρατία. This can be broken own into dêmos (the common people) and krátos (force or might). Under the ruler Cleisthenes in 508 BC we first have Athenian democracy. Since then the freedom of the people has been hard fought both for and against. In truth the default position for most of human history has been autocratic rule by monarchs and dynasties. Democracy is a fragile flower that is always in danger of withering and reverting to autocratic rule.

In this context it was Madame Germaine de Staël (1766-1817) French woman of letters to whom is attributed the description of Russian governance as ‘Autocracy tempered by assassination!’ In her own life her moderate and centrist political opinions who found her exiled both during the French Revolution ‘reign of terror’ and later by Napoleon.

The somewhat more esoteric organisation known as the Church of England for all its many faults has also in its Reformation history found itself virtually extinguished as a via media first under the 16th century Mary 1 and resurgent Roman Catholicism and then in the 17th century Commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell and the extreme Protestants. The renowned Richard Hooker in his ‘Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie’[ii]argued without actually using the tag via media for just that as the Anglican middle way. By and large this has continued to characterise Anglicanism in its ever-increasing world-wide diaspora.

It is only in relatively recent times that a lurch towards a new kind of ecclesiastical autocracy, based on conservative interpretations of scripture regarding sexuality and especially homosexuality, has threatened a schism within the Communion. This has enabled Provinces such as Uganda to support the enactment of ferocious anti-gay legislation.[iii] Whilst there is certainly a cultural element in this it is hard to imagine that the increasingly strident breakaway American Anglican Church of North America (ANCA) is not somehow associated with such views?

Thus far post-Reformation Anglicanism has never embraced the idea of either a Pope or a Patriarch. Although there have been periodic calls for the Archbishop of Canterbury to take on such a role, this is so unlikely as to be safely out of the question. Herein, perhaps after all, there is some hope that the type of Christian governance and theology characteristic of the Anglican world actually has a built-in resistance to autocracy. This then is a rare piece of good news, not exactly democracy writ large, but certainly a preference for the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

Nicholas Henderson

Editor: Anglicanism.org

Pentecost 2023

[i] https://freedomhouse.org/article/europe-and-eurasia-democracy-autocracy-gap-widening

[ii] Of the Lawes has been characterised as “probably the first great work of philosophy and theology to be written in English”. The book is far more than a negative rebuttal of puritan claims: it is “a continuous and coherent whole presenting a philosophy and theology congenial to the Anglican Book of Common Prayer and the traditional aspects of the Elizabethan Settlement”

[iii] https://international.la-croix.com/news/world/harshly-criticized-abroad-ugandan-anti-gay-law-pleases-local-anglican-church/17895