Whither Christendom in the New Year?

Whither Christendom in the New Year?

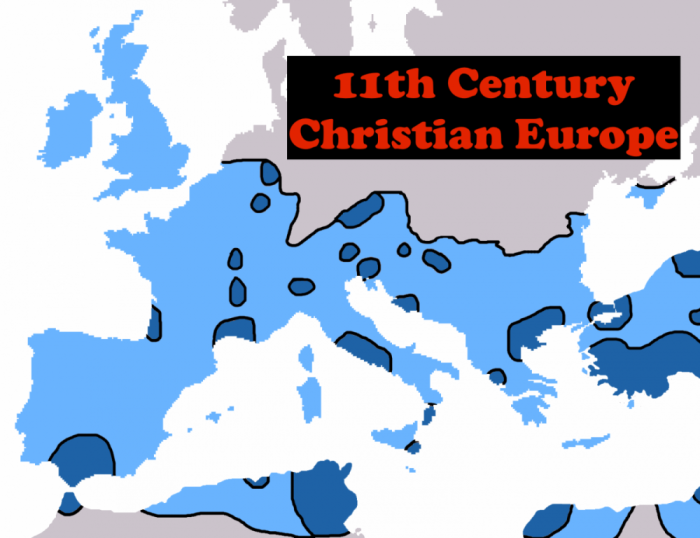

Historically ‘Christendom’ has had an approximation to the geographical area covered by the current European Union. The notion of Europe and the Western World has been intimately connected with the concept of Christianity and Christendom; many even attribute Christianity for being the link that created a unified European identity.[i] British Church historian Diarmaid MacCulloch described (2010) Christendom as “the union between Christianity and secular power”.[ii]

For the purposes of this editorial there is arguably a link between the idea of Christendom and the current European Union. Largely Christian in history and identity the twenty-seven countries that comprise the European Union have this as a commonality. Despite its very recent departure from the Union the United Kingdom shares this heritage.

The consequences of the long-haul and slow-motion separation of the United Kingdom from Europe as a political and economic organisation have yet fully to unravel. The narrow Brexit Referendum result in 2016 with a margin of only 3.87%, well within statistical variability and not conducted fully in accordance with international standards for referenda,[iii] has led to a persistent toxic and divisive culture. This is likely to define people for years to come despite clarion calls by the government to move on and pursue a new unity.

Interestingly, from the point of view of the Church of England at the time of the Referendum, the House of Bishops came out in favour of remain, whilst we are told that Anglicans voted by a two-thirds majority to leave.[iv] The social conservatism of the mythical person in the pew seems to have contributed to the swing in favour of departure. Indeed, the old adage that the C of E is a Telegraph and Mail reading people ministered to by a Guardian reading clergy, seems to have been borne out. At this point readers outside the United Kingdom are requested to bear with me as I briefly explore the consequent profound but parochial constitutional change.

The ramifications of what has now happened on New Year’s Day 2021 invite historical reflection. The United Kingdom was a union first mooted by James 1 of England (James VI of Scotland) in 1603 and styled under his sovereignty as ‘Great Britain and Ireland’. Much later this was politically endorsed on 1st May 1707 with the union of the Scottish and English Parliaments. Thus, for over three hundred years there was political stability, Ireland notwithstanding, until now.

The insidious rise, especially over the past decade, of English nationalism, which was probably the main driver for exiting the European Union, now threatens the eventual ‘break-up’ of the United Kingdom itself. Both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted remain and sentiment towards the Union is increasingly hostile particularly in Scotland. Northern Ireland meanwhile has been left stranded by the agreement to “put a border down the Irish Sea” something that Prime Minister Johnson said “no Prime Minister would ever do”[v]. Thus, post-Brexit the United Kingdom enters into a new period of uncertainty with an as yet unproven and potentially unfulfillable “we will prosper mightily”[vi] promise by the British Prime Minister.

Interestingly, in this context Anglicans in the European archipelago islands of the United Kingdom and beyond have long since established a modus vivendi of unity in political diversity. The five Provinces of Canterbury, York, the Church in Wales, the Scottish Episcopal Church and the Church of Ireland have encompassed, with a mutuality of interest, the proclamation of the Gospel without compromising local circumstances and priorities.

It would be wrong to style this ‘federalism’ as each Province is independent under its own Archbishop or Primus and synodical governance. The necessary unifying factor is ‘being in communion with the see of Canterbury’. This is, of course, disputed by conservative ‘breakaways’ busy trying to establish a new unity heavily based on a mutual abhorrence of same-sex relationships and, to bolster their argument, ‘all things liberal’[vii] as defined by American conservatives.

So, with a few exceptions, in Anglicanism it is possible to find echoes of a type of nationalism without borders. Could this be a model for the future of the United Kingdom outside the European Union? Anglicanism certainly has a place in Christendom and, for the time being whilst the inevitable long-haul back into the European Union takes place over the next couple of generations, it ought to speak with a clear unitive voice of reconciliation, encouragement and hope … ought to that is, although its leadership currently seems to have been struck dumb.

Nicholas Henderson

Editor: Anglicanism.org

New Year 2021

[i] Dawson, Christopher: Glen Olsen (1961) Crisis in Western Education (reprint. ed.) p. 108

[ii] MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2010). A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. London: Penguin Publishing Group. p.1024-1030.

[iii] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/RuleOfLaw/CompilationDemocracy/Pages/CoEGuidelines1.aspx

[iv] https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexit/2018/09/20/how-anglicans-tipped-the-brexit-vote/

[v] https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/uk/brexit-and-an-irish-sea-border-no-uk-prime-minster-could-ever-agree-to-it-1.4054338

[vi] https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/uk/johnson-uk-will-prosper-mightily-in-a-no-deal-brexit-1.4443255 Boris Johnson with shades of Land of Hope and Glory ‘God who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet!’

[vii] In short ‘liberal’ amongst conservatives in the United States has become a pejorative term, carrying the meaning of socialism, pro-choice rights and all things immoral. In the U.K. it means essentially generous, open-minded and understanding.