Dear Heart-broken, Dear Confused: Agony Aunts and Problem Pages as Implicit Religion

Dear Heart-broken, Dear Confused: Agony Aunts and Problem Pages as Implicit Religion

The Very Revd. Professor Martyn Percy, Harris Manchester College Oxford

The Very Revd Professor Martyn Percy was the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford from 2014-2022. From 2004-14 Martyn was the Principal of Ripon College, Cuddesdon, one of the largest Anglican ordination training centres in the world. He has also undertaken a number of roles with charities and in public life, including being a Director of the Advertising Standards Authority and an Advisor to the British Board of Film Classification. Martyn writes on religion in contemporary culture and modern ecclesiology. He teaches for the Faculty of Theology and Religion at the University ofOxford, and tutors in the Social Sciences Division and at the Saïd Business School. Martyn is currently an Honorary Fellow at Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford.

Such is the extent of secularization in modern Britain, it will now come as a surprise to quite a number of folk that modern hospitals have religious foundations – St. Thomas or St. Bartholomew come to mind. Also, Halloween seems to have morphed into a secular celebration of light-hearted horror- genres, replete with pumpkins. For most, the remembrance of all souls has become quite detached. The religious origins of Oxbridge Colleges and other educational establishments are perhaps easier to grasp. Though I do recall interviewing a student for entry into Cambridge some decades ago, who had declined Jesus, Christ’s, Trinity and other colleges because of their religious names but had chosen Emmanuel. I truly wish this were an urban myth, but it isn’t.

So, when teaching the sociology of contemporary religion, and trying to help students come to terms with normative practices, institutions and organisation in everyday life, many are surprised to discover the religious origins and purpose in football clubs such as Liverpool, Everton, Manchester City, Rangers, Celtic and more besides. It comes as more of a surprise to discover that the entire DNA of basketball was rooted in the late 19th century, with clergy and well-meaning Christians developing a (largely) non-contact sport for small church halls, to keep wayward inner-city youths exercised, absorbed, healthy and off the streets.

Contemporary celebrations of Christmas are similar, and it is undoubtedly the case that the modern Santa Claus was contriving by Tory New York High Anglicans engaging in some intentional social engineering. The Service of Nine Lessons and Carols – another Anglican invention – was Eric Milner-White’s answer to the appalling lack of Christian knowledge he had encountered amongst working class soldiers during the Great War. His Service of Nine Lessons and Carols was designed to tell the Christian story from Genesis to Revelation using rousing English folk melodies, hearty carols and no sermon, Also the Service was designed to last less than an hour. So, you see, long before Alpha Courses kicked in, enterprising clergy reckoned that an hour of scripture and song could get the gospel message across. I concur. [See: Martyn Percy, ‘Christmas in the Anglican Tradition’, in Tim Larsen (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Christmas (Oxford: OUP 2020, pp. 153-166)].

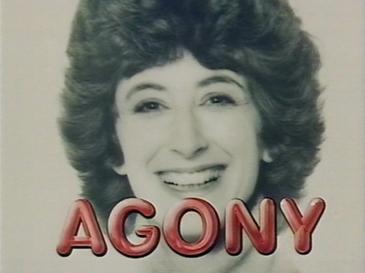

Agony Aunts

It will doubtless come as a considerable surprise to discover that the modern Problem Page was shaped and to some extent originated by religious roots and social, moral and spiritual concerns. John Dunton was a 32 year old printer and bookseller. It was during the winter of 1691, whilst out walking in the fields Lambeth, that he sought to wrestle with his conscience. He was, by his own admission, contemplating an extra-marital affair. For Dunton the matter remained one of torment, but the walk gave birth to an idea. Suppose he were to publish the nature of his anguish, and its consequences, using a letter with a pseudonym, and seek public advice on the right course of action? The device of audience participation in a moral dilemma was born, and first appeared on March 10th, 1691 in The Athenian Gazette. (The modern successor to such approaches in newspapers today often blends expert advisors with members of the public contributing insights and suggestions).

John Dunton (1659–1733) founded The Athenian Society to publish The Athenian Mercury, the first major popular periodical and first miscellaneous periodical in England. In 1693, for four weeks, the Athenian Society also published The Ladies’ Mercury, which was the first periodical published that was specifically designed for women readers. Dunton hardly lacked for religious interlocutors in his background. He could trace his roots back through several generations of clergy, and he himself was related by marriage (through his sister) to Samuel Wesley, the father of John and Charles.

Dunton was no kind of progressive post-Christian liberal. The established hierarchical order of religion and morality remained unchallenged. But even in the later seventeenth century, the ground was shifting. Theatre, opera, publications and entertainment both reinforced and challenged prevailing social, moral and intellectual norms. In an age of emergent Deism, few expected God to act as some kind of school headmaster, or the clergy as God’s prefects, to issue censorship and retribution. Increasingly, the moral judgment and social pressure of society played an important role in the ordering of society. The significance of Dunton’s initiative should not be underestimated, since this is the first record – in print, at least – we have of experts and members of the public commenting on personal social and moral issues that vexed individuals.

From the outset, we encounter the light touch counsel and occasional tongue- in-cheek chastening that we still find from Agony Aunts today. For example, one of Dunton’s correspondents wanted to know if it was permissible to pray to God that his wife might die – they had been separated for many years – in order that he might remarry? In the seventeenth century, “till death us do part” meant what it said. The Athenian tartly responded by stating that if [his] “wife were fit for heaven, then she is fit for you”, adding that it would be “handsomer to submit to God’s will and wait with patience”, before signing off with the mildly chiding suggestion that a better prayer might be to ask God to convert the parties into more lovable individuals.

Robin Kent’s illuminating Aunt Agony Advises – Problem Pages Through the Ages (London: W.H. Allen, 1979), provides us with an engaging study of the Problem Page as a kind of barometer and guide to the social and moral predilections and dilemmas that absorb individuals in wider society. Although these may not be our issues, they still direct us to the arenas of conduct and conscience that need settlement. Robin Kent identifies courtship, marriage and divorce as key issues in the 17th century. But also surfacing are issues of etiquette, personal medical issues, family dynamics and social stigmatisation (i.e., “blighted women”). Widows, spinsters and “ruined maids” frequently crop up as correspondents. Religion, spirituality, doubt and contemporary morality also feature strongly.

Reading the correspondence and counsel of Problem Pages from three hundred years ago gives us an illuminating insight into the vexing issues that individuals wrestled with then. Of course, these have changed over time. As the popularity of Agony Aunts and Problem Pages spread to mainstream publications, we find individual correspondents – and the respondents – capturing the emerging moral and social landscape of their time.

For example, the latter half of the twentieth century sees many Agony Aunts in national newspapers and magazines frequently grappling with sexuality. For the most part, the Problem Pages handle the anguish, torment, confusion and desires articulated with a fine blend of compassion, care, empathy and emotional intelligence, along with practical counsel and pragmatic suggestions. Yet even now, reading Problem Pages from just fifty years’ ago is a stark reminder of the social, personal and moral issues that many wrestled with.

Quite recently, I found myself studying some of the early editions of Gay News from 1979, and so published at the same time as Robin Kent’s study. To study Gay News forty-plus years on is to enter a world of stigmatization, marginalization, resilience, hope and determination. I was interested in how the Church of England’s early official reports on human sexuality had been received by the subjects of debate. The ever-gnomic Archbishop Robert Runcie commented that one report provided “food for thought”, and Gay News notes him speaking out publicly for “compassion”. Another Bishop – this is 1979 – is less irenic, and describes gay people as “corrupters of youth, sick and unstable”.

Problem Pages as Implicit Religion

The Letters Pages from a significant sample of Gay News provide us with a model of strong, gentle, considered, compassionate and caring correspondence. Moreover, in many respects, we are offered a mirror to what is offered by the Agony Aunts through their counsel. Here, I make some observations about the general nature of the advice, and where it fits within spirit of guidance.

First, and perhaps most obviously, Problem Pages are a virtual ‘confessional box’ in which the reader can overhear what is being poured out, and eavesdrop on what the remedy might be. Some confessions prompt chiding and censure. But many evoke compassion, empathy and caring – the kind one might reasonably expect from a therapist or counsellor. Much of the advice is non-judgmental, and returns agency and confidence to the correspondent. Indeed, what is striking about so many Agony Aunts is their capacity to range over moral, social and personal issues, yet without lapsing into some patronizing lecture.

Second, the terrain of presenting issues that Agony Aunts engage with is entirely cognisant with the open and ambivalent texture of pastoral counselling and conversation. Feelings of shame, guilt, inadequacy, grief, anger, confusion, resentment, bitterness and more besides are engaged with in a manner that is undoubtedly receptive, succinct, yet belies the wisdom offered. If Problem Pages are, effectively, a confessional, the respondent speaks over the head of the correspondent to the wider readership. We are offered a pulpit of intimacy; altars of transformational communion; an exchange of peace; conditional or fulsome absolution for the sin and shame that seems to cling so closely; and yet, received, heard and resolved, leads to healing and liberation.

Third, as John Hardy reflects (‘Overheard in Passing: Talking Weather, Funerals and Implicit Religion’, Theology, July/August 2017, Volume 120, no. 2, pp. 271- 278), even our ordinary weather-related discourse takes on a form of sublimated spirituality, hinting at the calming liturgical-like chant of the shipping forecast on BBC Radio 4, every midnight. It soothes us. Agony Aunts seem adept at comforting the afflicted, and occasionally afflicting the comfortable – the smug and self-righteous. Here, I am very struck by Emma Percy’s readings of the transformations captured in the Queer Eye TV series – kindness, care, attentive listening and discernment in the detail matter to those who are bound by social, moral or religious constraints that oppress. [See: Emma Percy’s essay in Fearful Times; Living Faith, (eds) Robert Boak Slocum and Martyn Percy, (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2021)].

Can it really be the case that Agony Aunts offer us something that can be ascribed to Implicit Religion? I think so, since their counsel constitutes a form of pastoral-chaplaincy in public space – be that the family home, workplace, bedroom or other arena. I think of the Doonesbury cartoon (by Trudeau, published in June 1993), where a soldier wounded in hospital after the first Gulf War and struggling with PTSD unburdens himself to another officer who is clearly a skilled listener and reflector. The wounded soldier asks if the officer is a Chaplain? The confidant replies that he is not, but instead should be regardedas the “Morale Officer” for those recovering from the trauma of war, and those made to witness this in their roles. Concepts such as morale, counsel, kindness and compassion may seem like common fare for the caring professions, but I hold them to have an intrinsic religious quality that offers an entirely different perspective on the ‘priesthood of all believers’. In the Problem Pages, we frequently find an almost ritualistic confession-counsel-absolution sequencing, not even lacking the gospel punchline “go, and sin no more”. What comes through the office of Agony Aunt is a delicate and reticulate blend of feminine, maternal, caring, listening, compassion, kindness and counsel. Agony Aunts are there to guide us – spiritually, morally, emotionally and pastorally – and they do so with an attentiveness that lends itself to an interpretative framework that would not be unfamiliar to those engaged in reading Implicit Religion. Implicit Religion as an Interpretative Lens.

Of course, I recognise that we are making use of a relatively rare sociological lens – that of ‘Implicit Religion’ (a term coined and defined by the late Edward Bailey [1935-2015]) – and analyse as Bailey might have done. Bailey was both a theologian and sociologist, and as an Anglican clergyman and academic, had an additional platform from which to assess everyday life. Implicit Religion, as a ‘lens’ for reading current patterns of social behaviour, simply refers to people’s commitments — whether they take a religious or secular form. [See Edward Bailey, Implicit Religion in Contemporary Society (Kampen, Netherlands: Kok Pharos, 1997). See also Edward Bailey, Implicit Religion; An Introduction (London: Middlesex University Press, 1998); Implicit Religion in Contemporary Society (Leuven: Peeters, 2006)].

I use the term ‘lens’ here with some care, as Implicit Religion is not a methodology, per se. In common with many other kinds of sociological outlooks, Implicit Religion is a ‘take’; a way of viewing the apparently ordinary and familiar. Implicit Religion is not like the lens of ‘Folk Religion’, which looks at specific acts of communal and individual spirituality that are largely outside the control of mainstream ‘religious’ activity. Specialists in the study of ‘Folk Religion’ usually focus on beliefs and practices that survive the imposition of official religious monopolies. Implicit Religion is an approach that is neither ‘civil’ nor ‘folk’ in broad outlook. It is, rather, an intentional focus on ordinary everyday activity that may appear, at first sight, to have no element of spirituality or religion to it whatsoever. Moreover, the participants may have no explicit idea that what they are doing can be read and understood as ‘religious’. So, their participation is often unconscious. Or, as Edward Bailey maintained, a matter of Implicit Religion.

What then, of Implicit Religion as a ‘lens’ for understanding Agony Aunts? Something that is implicit lends itself to eventual surfacing, and being made explicit. Following Bailey, I hold that the ‘lens’ of Implicit Religion is essentially ‘bifocal’ in character. It allows through an oeuvre or single aperture, to both focus on something that lies in the foreground, and yet also see something else that lies at a far greater distance.

In Bailey’s case, the bifocal lens of Implicit Religion permitted him to focus on immediate, ordinary everyday human activity. And the more distant subject was, as ever, the realization that we could not escape the horizon of secularization. Bailey’s bifocal lens brought the two together, and placed them in a single framework (or lens) for discussion. This approach “opens up the possibility of discovering the sacred within what might otherwise be dismissed as profane, and of finding an experience of the holy, within an apparently irreligious realm”. [See Edward Bailey, ‘Implicit Religion’ in The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion, ed. P. Clarke (Oxford: OUP, 2009) pp. 801- 816]. Bailey argued that the lens of Implicit Religion permitted several insights to come together as (what he termed) ‘integrating foci’ – the possibility of seeing ‘intensive concerns with extensive effects’, for example.]

Even more fruitfully, perhaps, concepts of Implicit Religion can act as a counterbalance towards the tendency to automatically equate ‘religion’ with specialized institutions, articulated beliefs, and specific religious behaviour. Above all, the lens of Implicit Religion allows us to read aspects of contemporary culture and conduct for nascent elements of religiosity within what, to the more casual observer, might conventionally be seen as a normative secular sphere. As Timothy Jenkins’ work has shown that the Implicit Religion lens can illuminate the simplest things in our communities. His description and analysis of a the mildly chaotic jollity of a community-led ‘Whit Walk’ in a suburb of Bristol is a perfect example of the Implicit Religion lens bringing a curious social phenomenon into sharper focus. [See: Tim Jenkins, Religion in English Everyday Life (Cambridge: Berghahn Books, 1999).]

Conclusion

Sociologists continue to narrate the fate of religion in the Developed World as one of believing without belonging; spiritual but not religious; of consumption rather than obligation. Whether or not this trajectory continues on some stable course, any portrait of religion receding in the 21st century has to reckon upon what is surfaced when the tide goes out. It is at these points that the new secular confessor-pardoner-pastors – as many Agony Aunts have now inhabited such roles – become visible reminders of the resilience of religion. Our age is not irreligious. All the evidence points to our constant and enduring quests.

Agony Aunts engage in the untidy and broken lives of others. They deal with the tears, aches and broken points of human existence, including shame, self- loathing, suicidal thoughts, heart-break, bereavement, aching loneliness, feelings of inadequacy, and a panoply of fears. Agony Aunts respond to those who struggle with the confusion of who they are and what they are becoming, in terms of identity, sexuality, gender – so many uncertainties and unknowns. In a world saturated with information and awash with communication, these open confessionals soothe, succour and support those who are feeling bereft, confused and exposed.

Happily, there is a parable to end with. In 1935, a young woman wrote a letter to Nursery World magazine, expressing her sense of isolation and loneliness. Women from all over the country experiencing similar frustrations wrote back. To create an outlet for their plentiful ideas and opinions they started a private magazine – The Cooperative Correspondence Club. The deep friendships formed through its pages ensured the magazine continued until 1990, fifty-five years after the first issue had been published. Jenna Bailey’s Can Any Mother Help? (London: Faber and Faber, 1994) captures the essence of these letters which testify to the value of shared counsel, wisdom and compassion.

Likewise, the modus operandi of Agony Aunts, and with their pastoral homilies through their Problem Pages, resonate with Implicit Religion: “intensive concerns with extensive effects”. Problem Pages represent a late-modern development that, but like hospitals and other institutions suggest a more hopeful outlook for faith. Secularization theses and ideological Secularism assume society is becoming less religious as it develops. However, those who choose to read and interpret the world through the oeuvre of Implicit Religion will find religion in unexpected places. Granted, that may be outside the domain of formal and official religion, and in the sphere of the informal and operant.

Yet, as hospitals undoubtedly know, basketball testifies, and Problem Pages and Agony Aunts witness, faith and hope signify an embedded ingredient within our ‘social mix’ – from the outset. One can no more separate out religion from society than remove the egg from a cake. It is always baked in…even if one can no longer taste and see it. Trust me on this. Religion, change, faith, forgiveness, love, redemption and the hope of God are ever-present. This is how we live.

Martyn Percy

Kingdom Season 2022