Loving the prophet… or maybe not

Mark Rudall explores how pastoral concern for a congregation may actually silence a prophetic voice

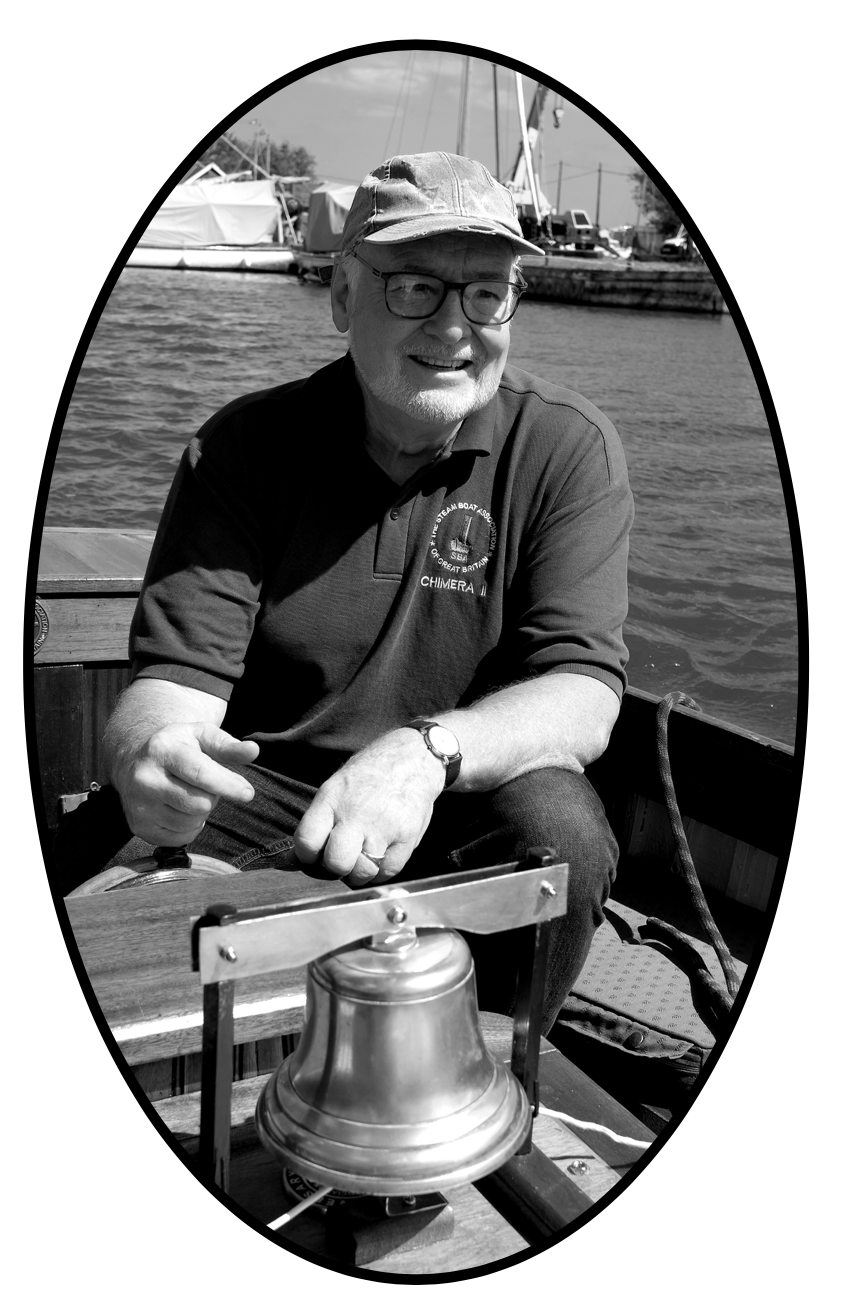

I was touched to read recently the biography of a man who has flown to the heights of UK politics but who told how, thirty years ago, he had faced challenges as a youthful member of a Christian charity’s communications team sent out to promote in supporting churches. He wrote ‘My team leader gently told me ‘You need to love your congregation…’

The Team Leader was me and I’d still give that advice, perhaps even more so now as, growing older, the circle has closed and preaching has become more and more challenging for me.

The Church of England has received many refugees from other traditions and I became an Anglican at the end of the 20th century when the idea of Christian life as an ongoing journey of discovery, truly a pilgrimage, took ever deeper root. Unable to espouse the ‘saved, and that’s it’ static condition so often portrayed by traditional evangelicalism, there was also an awareness after 23 years in non-conformist ministry of being in a scene that was teetering towards an unappealing and dangerous conservatism.

Thinkers like Brian McLaren and Richard Rohr from their different sides of the American Christian spectrum were already making an impact here in the UK. They wrote against a national background of rising radical conservatism and Christian nationalism sending any notions of ‘orthodoxy’ into a floundering spiral.

Indeed an American Baptist thinker David Gushee, has noted that many far-right US ‘evangelicals’ should really be described as ‘Christianist’ – on the same model as the term ‘Islamist’ describes dangerously violent and ill-informed followers of Islam. That may be overstating the case but I cannot unsee the news footage of a woman in Alabama sitting in her truck and pointing to two artifacts beside her on the passenger seat while saying to camera: ‘All I need is my Bible and my gun…’

With personal unease festering for some time it was a preaching series on the themes and people of Exodus promoted in my local parish church that brought me up against the buffers. I became deeply uncomfortable but not concisely able to articulate why, But of course Exodus shines a spotlight on the roots of contemporary Zionism. The stories highlighted how what was happening in Gaza had so many stark echoes of the Old Testament’s tribal conquest of the ‘promised land’ with its horrific wiping out of non-Hebraic people groups. That ‘Herem’ demanded the obliteration of men, women, children along with their livestock, all apparently sanctioned both then and now by the same God I worship as a 21st century Christian.

At the same time, from a tender age I have been horrifyingly aware of the unconscionable Nazi Holocaust which ended only eight years before my birth. Appalled too by the monstrous Hamas action of October 7th 2023, but at the same time knowing – and latterly seeing for myself – the effects of those 70-plus years of depredations by Zionist settlers on the West Bank which triggered that explosive Hamas action. To see all that followed by what the UN has called a genocide in Gaza, but to hear it justified by Zionists on both sides of the Atlantic is to face up to a series of irreconcilable dissonances screaming too loudly to be silenced by academic rationalisation.

Knowing that I could never provide the kind of simple moral teaching about Exodus heroes that would have been expected of me I was relieved when others volunteered to preach but felt that I had been a coward of the first order.

I love the congregation in my parish church and as a long time member of the congregation many know me well and reciprocate it. I have to ask myself if I was truly loving them in not sharing the prophetic challenge tearing me apart, simply because I had no wish to rock any boats and set up tensions in an otherwise harmonious fellowship. Ours is an age which has effectively crushed free speech with regard to peoples and political movements in the Middle East. Furthermore, any psychologist who has studied attitude change in the context of religious faith will testify to the practical impossibility of influencing the long-held convictions of anyone much post age 25-30, hence the durability of cults and conspiracy theories.

Thus the tension remains between a personal desire to always encourage others, as a retired priest, or to launch a cruise missile into their midst.

My conviction that in mainstream Christianity there is no room for Zionism despite the baleful persuasion of fundamentalist teaching over the last 120 years, will simply fall on deaf or hostile ears: truly an Isaiah 6 vv9 &10 situation! Although to a much lesser degree than their cousins in the USA, many British evangelicals are also much influenced by fundamentalist teachings which see all 66 books of the Bible as a single inspired entity. The result of that has been a tendency to quietly forget that the people of Christ are New Testament people.

As a young theological student starting New Testament Greek, an early acquisition was a rather necessary little book with its title on the spine in Greek letters: ‘H KAINH ΔIA ΦHKH’: ‘The New Covenant’. It was a revelation to me as the word ‘Covenant’ is, to a modern English speaker, so much more loaded and powerful than the word ‘Testament’. A testament might be merely a report or a declaration but the word ‘Covenant’, in this context was overlaid with the ideas of ‘promise’ and ‘future’ derived directly from Jeremiah 31.31, and the promise of a New Covenant that God will make.

For Christians that Covenant sees its fulfilment in the coming of the Son of God because God ‘so loved the world’. God’s love, as seen in the gift of Jesus to the world and as also vigorously reinforced by St Paul, was no longer about a single nation: it was about the world, Jews and Gentiles alike.

Sadly the unravelling of generations of accepted teaching cannot be achieved by just a few angst-ridden preachers, some of them, like me, possibly considered past their Use-By date. There has to be a major revolutionary movement to refocus on the way the followers of Christ understand themselves, and the Bible.

I suggest that maybe one of the biggest challenges now facing the Church – amidst all the others – is how to haul us back into that understanding, so that we can start, once again, to concentrate on the uniqueness of Jesus, of who we are as his followers, and to actually hear clearly and be moved to act on what he taught.

So yes: I still want to love my congregations in the name of Christ. But as I go about it I know some will most certainly find it harder to love me.

Mark Rudall, January 2026

(The Revd Mark Rudall is a retired priest

and former Diocesan Communications Director

living in Hampshire, U.K.)