Paul Oestreicher reflects on being a gadfly

GADFLY

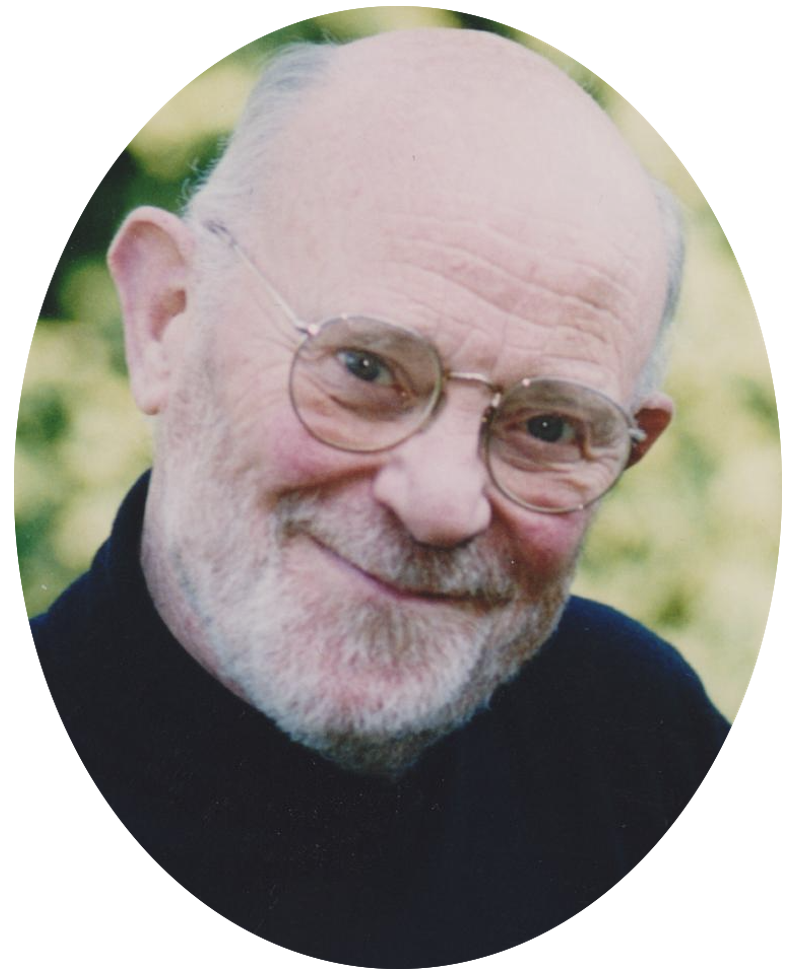

Canon Dr. Paul Oestreicher is an Anglican priest and Quaker political scientist, human rights activist, and peace campaigner, one-time Chair of Amnesty International UK, and still Vice-President of CND UK. He currently lives in Aotearoa New Zealand where he grew up as a refugee from Nazi Germany.

In 1984 my election as Bishop of Wellington in New Zealand made the English newspapers. A day or two later a postcard arrived from Francis House, whom I’d never met. It simply said “Don’t go. You are the gadfly our Church cannot do without.” I was puzzled. Who was this Francis and what is a gadfly? With so much on my mind, I put the card aside, but not for long. A gadfly, I soon learned, was a troublemaker who, more popularly, puts a cat among the pigeons. I should have known that House was a brilliant and wise ecumenical figure, rivalling George Bell of Chichester. The BBC had made him Head of Religious Broadcasting, only for him to be sidelined by his Church and sent well clear of Whitehall and Lambeth, to be Archdeacon of Macclesfield. Another Bell was too much. He might frighten the royal horses: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2004/sep/11/guardianobituaries.secondworldwar

As for Wellington, I still had to accept the election or reject it.

Then, a phone call. It was my fellow student and priest, Paul Reeves from his London hotel, the first Māori and first bishop to be chosen as New Zealand’s next Governor General, in effect the Head of State. “Will you two come and have dinner with us tonight? We are having lunch with the Queen and Princess Anne.”

That dinner, at the New Zealand taxpayers’ expense, went on far into the night. The lunch had unexpectedly been great fun. Paul, now Sir Paul, really wanted to talk about the Wellington bishopric. My wife and I had good reasons to say no. Sir Paul had compelling reasons to urge us to say yes. I had a great deal to pay back to New Zealand, where I’d grown up as a German refugee. With all our children in England, we were assured that Wellington need not be a lifelong commitment.

We should have realised how controversial my election was. By the New Zealand rules, the other dioceses had to ratify the election or, however unlikely, turn it down. In New Zealand it became a matter of public debate. The Bishop of Nelson successfully campaigned against this ‘Anglican Quaker’. Privately, the previous bishop rejected all that I stood for. Wellington would have to think again. Rejected I was. It came as a shock but on second thoughts as a huge relief. Much later, I thanked Peter Sutton for doing the right thing, even if for the wrong reasons.

My mind went back to that postcard. Had Francis House not challenged me to use my prophetic gifts more effectively in the Europe of which England and its Church is an inescapable part? In the cross currents of the old world into which I was born I would have to go on accepting rejection and, if need be, even affirmation. The Archbishop’s Appointments Advisor sent me to head up Coventry Cathedral’s Centre for International Reconciliation. “That is where you belong.” he said. My dream job?

The New Zealand episode added helpfully to my not uncommon spiritual acceptance of rejection. As a privileged BBC features producer, the Rector of Hampstead Parish Church offered me an honorary curacy and a family home in the beautiful old schoolhouse. Great, until his PCC forced him to back out. I would lower his Church’s tone by mixing with the coffee bar crowd. In fact, these good people were afraid that my pacifist politics might catch on.

Much later, the Archbishop of Canterbury offered me the post of Rector of St Mary-le-Bow, the City of London’s parish church, financed by the wealthy Grocer’s Company. I met these powerful businessmen. It was laughably tragic. “Canon, don’t you think you would upset the City’s apple carts?” My response, “Not half as much as Jesus, overthrowing the tables of the money changers in the Temple forecourt.” Blank faces.

The Archbishop sent me a second letter: “Paul, I apologise for making you this offer. The job is yours, but I don’t think you should waste your time in a war with these bankers.” I chickened out.

It was in the radical climate of 1968 that Bishop John Robinson of Honest to God fame offered me the job of Vicar of the smallest church in the Diocese of Southwark, The Ascension, Blackheath, my first and only parish. The Church was a classical gem built in 1697 as the private chapel of the Earl of Dartmouth. A miniature of St Paul’s Cathedral, built by a pupil of Christopher Wren. John Robinson hoped it might become a cultural oasis in a desert of the surrounding conservative parishes. He hoped this might dovetail with my other commitments, like chairing the British Section of Amnesty International. That would stimulate the parishioners, widen their horizon. The annual Amnesty book sale became highly successful.

Prophecy, topping St Paul’s list of the varied gifts given to God’s people, (Romans 12:6 ) is not naturally at ease with pastoral care. Early on, I met the housekeeper of the Diocesan Retreat next door. Deaconess Elsie Baker had felt called to the priesthood from her nineteenth year. In her late fifties, that was still beyond her reach.

“Elsie, I will put you in charge of the pastoral work of this parish. If you need help, ask me for it. It is in your hands.” We both felt liberated. The parish was happy. A decade later, Elsie preached in St Paul’s Cathedral. Aged 81, she was ultimately the oldest woman in England to be made a priest in the first ordination of women. The Bishop said, “God made you a priest long ago, but I will confirm it.” As I write, Sarah Mullaly is, in this secular age, about to become head of the Church as it struggles to survive. Some light in our darkness.

Bob Whyte came to me, trained in Cambridge for the priesthood. As a young Maoist, he doubted whether any bishop would ordain him. “My bishop will” I said, “provided you are true to yourself.” He and his wife Maggi created the Blackheath Commune, studied the history of Christianity in China and took many people to China, church leaders included. Bob combined that with commitment to the parish. Within a few years, he was the China Secretary of the British Council of Churches, writing a history of Christianity in China. When the fascist National Front staged a demonstration demanding this ‘Communist curate’ be removed, far from that happening, Bob hired a human rights lawyer and had a local detective prosecuted for harassing a mixed-race parish family. Faith and action held hands.

In 1981, our parish commemorated The Peasant’s Revolt of 1381. On Blackheath, Wat Tyler and his priest John Ball had summoned the peasants to march on the King’s palace during the reign of Richard ll. John Ball preached that God wills, all shall be equal.

On Blackheath, in 1981 Robert Runcie, then Archbishop of Canterbury, on the back of a truck, celebrated a memorial eucharist. King Richard had said. “You who seek equality with Lords are not worthy to live. Serfs you will remain, but incomparably harsher. May your slavery be an example to posterity”. Tyler and Ball were, with the Church’s blessing, hung, drawn and quartered.

One thing at The Ascension was unique. We decided never to close God’s House by day or by night, leaving it open to the men of the road, lit behind a welcoming glass-fronted door. The police soon rang the vicarage bell. “Vicar, you have forgotten to lock up.” The colder it got, the more came to sleep. Our church vandalized? Never. A stolen cross was remarkably returned, found by a fisherman in the Thames at low tide. Endless vicarage tea. Albert came and stayed for three years, a virtual caretaker, until Lewisham Council gave him his own flat.

The best of music mattered. An apprentice organ builder, now well known, built his first all-purpose, good for Bach, instrument in the gallery. The liberal historian Lord Altrincham, who gave up his title to became plain John Grigg, scandalised the nation by criticising the Queen and incidentally our sermons across the road from his home.

I was then, and remain today a Vice-President of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. At my high school on the day after Hiroshima, our physics master said to us boys: “Either we now abolish war, or war will abolish us.” That day has come even more perilously close.

Did I, did we, come a little closer to fulfilling John Robinson’s dream of our becoming a prophetic oasis?

Maybe I spoilt it. Eric, our then priest worker, a local accountant, thought so. When much later, in his view, I had thrown out my principles by accepting an OBE for my work for ‘peace, human rights and the Church’, Eric – in much ruder words – told me to get lost.

Was Eric right? God knows.

Paul Oestreicher

26th January 2026

SS Timothy & Titus